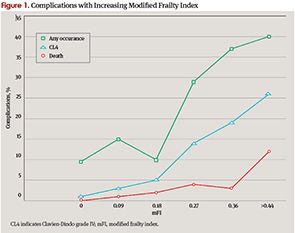

“What we found was, frankly, astounding,” Dr. Stachler said. “As the mFI score reached 0.45 or higher—that is, approximately 5 of 11 variables present—mortality increased from 0.2% to 11.9%.” Moreover, the risk for grade IV complications, such as post-operative septic shock, myocardial infarction, and pulmonary embolism, increased from 1.2% to 26.2%, he reported. The risk of all complications increased from 9.5% to 40.5% (P<0.001).

Explore This Issue

August 2014“The frailty index proved to be a very powerful predictive tool,” Dr. Stachler said. “In fact, it did a far better job at predicting morbidity and mortality than the historical variables we all tend to rely on—wound class, physical status, and age.”

The overreliance of some physicians and surgeons on age is something that Dr. Stachler said couldn’t be overstressed as a pitfall. “As we made clear in our paper, physicians are way too accustomed to thinking of age as an important predictor of complications when, in fact, frailty is likely the strongest predictor.”

Poised for Prime Time?

Dr. Stachler’s presentation was part of a Triological Society annual meeting session that explored “Issues You Cannot Ignore in Older Patients.” The reaction he got from attendees was that this FI data certainly should not be ignored, he said.

But should it be put into clinical practice? “To some degree, yes, but it does need some further tweaking and validation,” Dr. Stachler said. Once that is done, he noted, a next step might be to develop algorithms that surgeons can use to individualize therapy based on a patient’s unique mFI score. If, for example, a patient’s score indicates a higher risk for post-operative stroke or heart attack, “even before that patient reaches the OR, our team can use the algorithms to develop individualized post-operative care for those patients,” Dr. Stachler said. Such a strategy, he said, can’t help but make better physicians and surgeons for otolaryngology patients.

That scenario is very appealing to Jonas T. Johnson, MD, Dr. Eugene N. Myers Professor and Chairman of the department of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. Dr. Johnson said that he and his colleagues “are on track in helping all surgeons better understand techniques we might employ to enhance personalized medicine.” He added that he was introducing a study at the University of Pittsburgh to see if they can corroborate Dr. Stachler’s results.

If validated, Dr. Johnson said, such a tool could help address an important challenge in geriatric medicine: how to limit surgery and other interventions to patients who can truly benefit. “The majority of healthcare dollars are spent on terminal illness,” he said. “Also, 75% of people have surgery in the last year of their lives, and, when polled, most Americans respond that they would refuse surgery under this circumstance. Of course, physicians are in the business of trying to help. But is it possible that, in our efforts, we are actually hurting some people, or perhaps subjecting them to interventions that are doomed to fail?”

Leave a Reply