TKTK/SHUTTERSTOCK.com

An advisory panel to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recommended that physicians who prescribe opioid painkillers should receive training on the risks of overusing immediate release (IR), extended-release (ER), and long-acting (LA) formulations of pain medications. The committee made the endorsement following a hearing held May 3–4, 2016, in which its 30 members unanimously voted to revise current ER/LA opioid analgesic Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS).

Explore This Issue

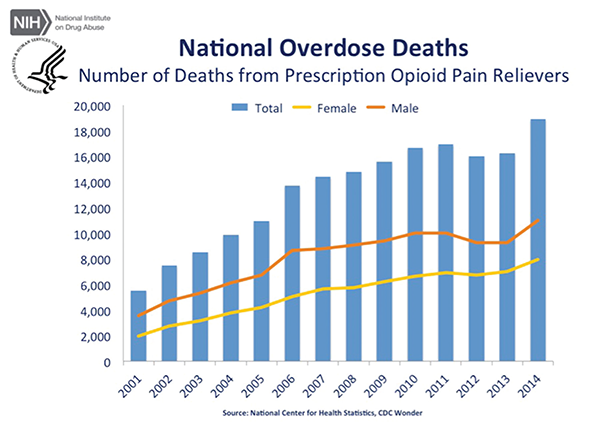

June 2016The panel made the recommendation amid an epidemic of deaths resulting from and addictions to opioid painkillers in the United States. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost 19,000 deaths involved prescription opioids in 2014—an increase from approximately 16,000 deaths in 2013.

In commenting on the recommendation, Anna H. Messner, MD, professor and vice chair, and residency program director of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Stanford Children’s Health in California, said, “It is very important for otolaryngologists to understand the benefits and limitations of any type of medication that they prescribe regularly. If the training helps to decrease the amount of opioid abuse and leads to fewer otolaryngologists prescribing narcotics when it’s not necessary, then it’s a good thing.”

Dr. Messner doesn’t think the training will have as much of an impact on pediatric otolaryngologists, however, because a recent black box warning from the FDA cautions against treating children who have sleep apnea with codeine. “Now we mostly use a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen to treat young children with post-tonsillectomy pain and recommend narcotics (excluding codeine) for breakthrough pain in older children and teenagers,” she said.

Source: Courtesy of National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Along these lines, Edward J. Damrose, MD, FACS, an otolaryngologist and vice chief of staff at Stanford Health Care, doesn’t think handling the issue as a one-size-fits-all approach will work. “While this problem affects all medical doctors, individual boards should administer and tailor this training to their members,” he maintained. “Otolaryngologists, who mostly manage acute surgical pain and not chronic pain, play a relatively small role in this national problem. Their training should focus on the field’s needs, such as the risks of death associated with opioid use in children and best practices in managing patients with pain from terminal cancer.”

Dr. Damrose also said that these new recommendations counter prior concepts, such as those outlined in the 2001 California legislation requiring mandatory opioid training for medical doctors. “The legislation emphasized the theme of underprescribing opioids for pain management and explored potential penalties for physicians who failed to medicate adequately,” he said. “We are now seeing the unforeseen consequences of this well-intentioned, but problematic, legislation.”

A Closer Look at the Recommendation

The two committees that comprised the panel—the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and its Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee—made the recommendation because members felt that the FDA’s current opioid REMS program, which has been in effect since 2012, was unsuccessful. The program asked clinicians to voluntarily complete continuing medical education courses to learn about the risks associated with long-acting opioids.

David Smart/SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

According to Committee Chairperson Almut Winterstein, PhD, chair of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Committee and professor and chair of pharmaceutical outcomes and policy at the College of Pharmacy at the University of Florida in Gainesville, “Voluntary training under the current REMS has only been able to reach about 20% of all opioid prescribers. Most committee members felt that the only way to accelerate the process was to make the training mandatory.”

Joanna Katzman, MD, MSPH, director of the University of New Mexico Pain Center and a neurologist with University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center in Albuquerque, was invited to speak to the panel because of her experience with mandatory prescribing regulations. Dr. Katzman said the FDA’s current program doesn’t provide enough education on short-acting opioids or pain management. “These topics are important because, like long-acting opioids, short-acting opioids have risks associated with them,” she said. She added that the FDA’s program hasn’t reduced the number of opioids that have been prescribed or the number of deaths due to drug overdoses.

Dr. Messner believes that otolaryngologists would most benefit from increased knowledge about postoperative pain management strategies. “Historically, otolaryngologists relied almost exclusively on narcotics as the foundation of a pain control plan,” she said. “Now we know that there are alternative medications and pain control strategies that result in better pain control, without the risk of narcotics.”

Some panel members also suggested that clinicians be trained in best practices of pain management, that training be tied to recently released CDC guidelines, and that it involve mental health and suicide screening. “There needs to be education around safe prescribing methods, because, over the past decade, many physicians have become used to writing prescription refills without realizing the consequences of some patients becoming dependent on medications,” Dr. Katzman said. “By giving physicians such as otolaryngologists information regarding alternatives to opioid medications, such as non-opioid medications or other non-pharmacological modalities, such as speech and physical therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units, and even behavioral interventions, they will have other options for treating patients who are in pain after having surgical procedures.”

Dr. Katzman also said it is incumbent upon healthcare professionals to learn how to screen patients so that they can prescribe a safe number of painkillers. “Most people who die of an unintentional opioid or heroin overdose get medications from a friend or relative,” she said. “These friends and relatives usually receive their medications from one doctor.”

What Training Might Entail

It’s now up to the FDA to decide what the training will entail and when it will become effective. Dr. Katzman said the FDA could implement a mandatory REMS program or consider other options, such as working with the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration to enforce it or making continuing medical education a requirement to renew a medical license. The FDA could also suggest that individual states impose the mandate through medical licensing boards.

Dr. Katzman would like to see many components of the current REMS program continued, including having physicians educate patients about drugs with associated risks. “They should determine if the risks outweigh the benefits,” Dr. Katzman said.

Dr. Katzman recommends that FDA-mandated training be modeled after a program adopted by the New Mexico state legislature in 2012. Initially, it required clinicians to take five hours of training in pain management and screening for addictions within 18 months. Then, whenever a healthcare provider renews his or her medical license, they must complete another five hours of opioid education. “The bill was passed because New Mexico has led the country in the number of overdose deaths, due to both prescription opioids and heroin,” Dr. Katzman said. “We viewed this as a public health crisis.”

“Our model has had positive effects in terms of dispensing fewer long-acting, high-dose opioids (the most dangerous opioids) and benzodiazepines (which are very dangerous when combined with opioids) and on overdose deaths,” said Dr. Katzman, who reports that the University of New Mexico studied the outcomes of the legislation and published them in the American Journal of Public Health in 2014.

According to the study, the bill resulted in a 16% reduction in opioid dispensing, especially high-dose opioids, and a 13% reduction in benzodiazepine dispensing. During the two years following the training, the number of deaths caused by opioid overdoses decreased; only in 2014 did an increase in total drug overdose deaths occur. One hundred of them (the majority) were due to methamphetamine abuse, not opioids (Am J Public Health. 2014;104:1356-1362). “The numbers have remained fairly stable, so we think the education is working,” Dr. Katzman said. “Furthermore, we saw a significant improvement in clinician knowledge, confidence, and attitudes from before taking the course compared with afterward.”

“Opioid misuse and abuse is a huge issue,” added Dr. Winterstein. “It will require a multi-modal approach to get it under control. I support mandatory training because a lot of evidence about pain management has developed over the last few years that prescribers may not be aware of. I think the training will raise awareness of its complexity and ensure that everyone is apprised of current best practices for pain management.”

Karen Appold is a freelance medical writer based in Pennsylvania.

Recognizing Drug Addition or Abuse in Patients

A physician can gather a great deal of information by asking a patient a lot of questions. “By talking to a patient and finding out about their psycho-social history, including whether or not they have a history of addiction, depression, or anxiety, as well as a family history of substance abuse, a clinician may be able to determine if a patient is a suspect for drug addiction or abuse,” said Dr. Katzman.

Furthermore, clinicians can choose from a host of validated screening tools (surveys) that take less than five minutes for a patient to fill out at a clinician’s office.

If a clinician suspects drug addiction or abuse, urine toxicology screens are very effective, Dr. Katzman added. “You can see if the patient is actually taking the medication as directed and if it is working. If not, you may suspect that the patient took all of the pills early on, or perhaps sold them on the street.

Another way to ascertain whether or not a patient is taking painkillers as prescribed is to perform random pill counts. “Call the patient and request to see them in 24 hours to make sure that they still have the proper number of pills remaining,” Dr. Katzman said. Or, you could request that the patient sign a controlled substance agreement. Although it is not legally binding, the agreement can be educational for the patient and create a partnership between the patient and physician.

On a related note, in an effort to reduce prescription abuse or diversion (i.e., channeling drugs into illegal use), prescribers and pharmacists can employ a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP). This involves using a state-run electronic search engine to find out if a patient has already been prescribed a controlled substance by another physician. “If a clinician finds this to be the case, this could identify the patient as high risk and alert the clinician to not prescribe additional postoperative medications,” Dr. Katzman said. PDMP is available in all states except Missouri.—KA