Most people will experience some degree of hearing loss as they age. Statistics from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders at the National institutes of Health (NIH) indicate that 30 percent of adults ages 65 to 74, and 47 percent of adults 75 years or older, have hearing loss.

Besides these findings, there is a paucity of data on the effects of hearing loss on older adults. Much that is known about the psychosocial effects of hearing loss on older adults comes from a 1999 report by the National Council on Aging (NCOA), which found that untreated hearing loss is a prevalent and serious problem among hearing-impaired older adults.

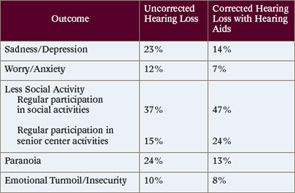

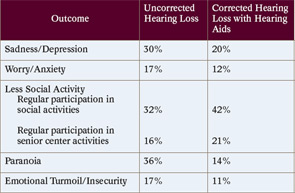

Compared to older adults with corrected hearing impairment, the NCOA study found that older adults with untreated hearing impairment were more likely to experience sadness and depression, worry and anxiety, paranoia, less social activity and emotional turmoil and insecurity. The percentages of patients with mild hearing loss reporting these outcomes are shown in table 1 (p. 5), while those with more severe hearing loss are shown in table 2 (p. 5).

Despite evidence of the detrimental effects of even mild hearing loss on older patients, the numbers of older people correcting hearing loss remain woefully low. This is true even though studies clearly show the benefits of hearing aids for people who wear them, as reported more recently in 2007 in the American Academy of Audiology’s systematic review of the literature on the effects of hearing aids on health-related quality of life outcomes. The report found that hearing aids improved quality of life in hearing-impaired adults by reducing the psychological, social and emotional effects of hearing loss (J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18(2):151-183).

The reason for the lack of better hearing loss correction appears to be multifold. According to the NCOA report, denial on the part of the hearing-impaired person is a primary reason. Additionally, cost issues and the difficulty involved in getting used to wearing a device can be major challenges. A more subtle problem may be the perception by many physicians, as well as older hearing-impaired adults themselves, that hearing loss, and even the psychosocial problems associated with hearing loss, are simply a part of aging.

Recent research on a possible connection between hearing loss and cognitive decline may provide a stronger impetus for both physicians and patients to seek help for hearing loss.

Source: National Academy on Aging; hearingoffice.com/download/untreatedhearinglossreport.pdf

Hearing Loss and Cognitive Decline

Luigi Ferrucci, MD, PhD, a geriatrician and epidemiologist and director of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging at the National Institute on Aging at the NIH, Baltimore, believes that hearing loss in older people is now being looked at in a broader framework than in the past.

Instead of concentrating on aging in the last period of life, Dr. Ferrucci said many geriatricians and gerontologists are now focusing on a life perspective risk factor exposure from birth and afterward to explain the large variability in older persons with regard to their ability to cope with stressors.

“We have been looking at a number of factors that can influence and motivate this ability to be resilient to stress and respond through compensatory mechanisms,” he said. “Of course, the ability to communicate and to interact are important issues that affect the plasticity of the brain. Thus, we had the idea of using data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study on Aging (BLSA) to see whether hearing loss in young and adult age affect the way people aged in terms of physical and cognitive function.”

The multidisciplinary study, conducted in collaboration with Frank Lin, MD, PhD, assistant professor of otology, neurotology and skull base surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, is the first to explore the hypothesis of an association between hearing loss and cognitive decline, including dementia and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Although publication of study details is embargoed until February 2011, Dr. Lin said that the results support an independent association between hearing loss and the risk of developing dementia over time, adjusting for confounding factors such as age and comorbidities.

Source: National Academy on Aging; hearingoffice.com/download/untreatedhearinglossreport.pdf

Speculating on the possible reasons for this association, Dr. Lin said that one possible pathway linking hearing loss with dementia is that hearing loss leads to cognitive load, and cognitive load decreases cognitive reserve. “Cognitive reserve is the phenomenon postulated to explain why some people can tolerate more pathology before they show signs of dementia,” he said. If cognitive reserve is decreased in people with hearing loss, then that may be why their dementia is expressed earlier than in a person with greater cognitive reserve.

Another pathway to explain this association, he said, is the possibility that hearing loss causes problems in communication, which cause social isolation, which then causes dementia. “The link between social isolation and dementia is established, but noone knows the pathophysiology behind it yet,” he said. A third pathway may be the possibility of a common pathology underlying hearing loss and dementia.

“The key thing is that none of these three pathways are mutually exclusive and it would be difficult to prove that one is completely wrong and one completely right,” Dr. Lin said. “I think there will always be a combination of the three depending on who you are and what caused your hearing loss.”

For Dr. Ferrucci, finding an association between hearing loss and dementia is not without consequences. “If a connection with dementia is linked to lack of communication and neuroplasticity, then correcting the hearing loss will improve the chance of not developing dementia or cognitive decline,” he said.

Dr. Lin also sees the implications of this research as having a dramatic impact on the “horrible disease process” of dementia. “The prevalence of dementia doubles every 20 years, so that by 2050 about one in 45 Americans will have dementia,” he said, emphasizing that even delaying the onset of dementia by one year will drop the prevalence by 10 to 15 percent 40 years from now.

“If hearing loss is associated with dementia, then the natural corollary is that if you intervene with a hearing aid or cochlear implant, then perhaps you could delay the onset of dementia,” he said.

—Bill Dickinson, AuD

A Relatively Easy Fix

The benefits of hearing aids for people suffering from hearing loss are well established and are sufficient for most people with hearing loss, except for those with severe or profound hearing loss, who may benefit more from cochlear implants.

According to M. Jennifer Derebery, MD, associate at the House Ear Clinic, Inc. and clinical professor of otolaryngology at the University of Southern California School of Medicine in Los Angeles, surveys show that over 8 percent of hearing aid wearers are quite satisfied with their hearing aids. Only a small percentage of people who actually need hearing aids use them, however.

Bill Dickinson, AuD, assistant professor in the department of hearing and speech sciences at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tenn., pointed to data showing that only about 40 percent of Americans reporting moderate to severe hearing loss wear hearing aids, a number that drops to only 9 percent in people with mild hearing loss (Hear Rev. 2009;16(11):12–31).

For Dr. Dickinson, compliance is dependent upon ensuring that the chosen device is appropriate and efficacious, producing the needed benefit for the patient. Thus, he emphasized, the focus needs to be on the efficacy of the device and not on the effectiveness of the device, which is defined by whether the device is capable of doing what it was designed to do.

“If a hearing aid is incorrectly chosen or inappropriately programmed, then the result will be a device that has high effectiveness and very low efficacy,” Dr. Dickinson said. Given this fact, he emphasized that only audiologists with experience in hearing aids and related technologies should select and fit hearing aids.

Another factor that may influence compliance, one that is often cited as the main reason for noncompliance, is their cost, because most people will have to pay for them out of pocket. However, the effect of cost on usage, said Dr. Lin, is diminished when looking at data from Europe, where national health insurance does cover hearing aids, and usage is similar to the U.S.

Another issue is simply the lack of recognition on the part of patients of the benefits they could derive from hearing aids. In addition, otolaryngologists and other physicians who see patients with hearing loss may not understand the detrimental consequences of untreated hearing loss.

“Hearing loss is a slow, insidious process, so people get used to it but not necessarily in a good, adaptive way,” said Dr. Lin, adding that when people do finally try a hearing aid, and it does not immediately work perfectly, they stop using it.

What is needed, he said, is improved counseling on the time, patience and training it takes to adapt to a hearing aid in order to gain its benefit. “Audiology studies show that the rate of hearing aid use skyrockets by just expending a bit more energy on counseling,” he said.

Otolaryngologists, he said, can learn from ophthalmologists who have developed approaches to vision rehabilitation for people with macular degeneration that could be a model for hearing loss rehabilitation. Citing a program at Johns Hopkins that uses occupational therapists dedicated to vision rehabilitation, he emphasized that otolaryngologists lack anything equivalent for hearing loss.

“We are behind ophthalmologists in their approach to vision rehabilitation, but that is where we could go in this field,” he said.

Leave a Reply