Figure 1. Right neck subdermal plaques with focal overlying ulceration.

Presentation: An 88-year-old male with an extensive medical history, including diabetes mellitus, presented to a tertiary care institution after being unsuccessfully treated for facial cellulitis. Three months prior to admission, he had developed a pruritic, edematous, and erythematous lesion on his left chin after he nicked himself shaving. He was treated on an outpatient basis by his primary care physician with a combination of topical and oral antibiotics. He was seen by dermatology, and superficial biopsies were performed, revealing only cellulitis with necrosis.

A month after the initial symptoms developed, the patient noted progression and was seen in an outside hospital. A facial CT scan was performed and was consistent with cellulitis without fluid collection. The patient was started on ceftriaxone and ten days of vancomycin with modest improvement of his facial swelling and edema. Despite treatment, he was admitted with worsening facial symptoms, development of pain, and serosanguinous drainage.

Blood cultures were negative, and wound cultures revealed rare mixed gram-positive flora. No leukocytosis or eosinophilia was present. After four days with no improvement, he was transferred to the tertiary care institution for otolaryngology evaluation.

Physical examination revealed honey-colored exudate over the lesion, with extension to the right side under the chin and a right submandibular mass concerning for pathologic cervical lymphadenopathy. Erythema and peripheral crusting with central ulceration at the area of the left jawline and the lower lip (Figure 1) were present. There was a subdermal plaque at the level of the left thyroid cartilage with medial soft tissue fullness and a firm, mobile plaque with overlying erythema and minimal ulceration. There was significant concern for malignancy due to the fungating appearance with subcutaneous extension. Deep biopsies of the left facial lesions and a fine needle aspiration of the right submandibular mass were performed.

—Tristan Klosterman, MD, Adam Bied, MD, Ramsay Farah, MD, and Amar Suryadevara, MD, Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y.

What’s your diagnosis? How would you manage this patient? Go to the next page for discussion of this case.

Histopathology examination revealed eosinophilic cellulitis. The fine needle aspiration was significant for scattered leukocytes and stroma. The patient was started on oral doxycycline and prednisone, 40 mg a day, with a daily topical Biafine foam dressing. Significant clinical response was seen at two-week follow-up, with near complete resolution at one month. He was tapered off the prednisone at that time. At six months, there were no clinical signs present.

Discussion

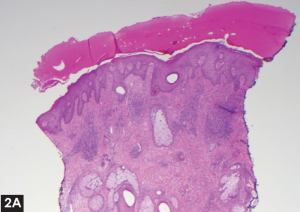

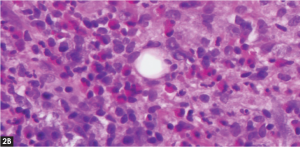

Diagnosis of eosinophilic cellulitis is obtained by a combination of clinical presentation andhistopathologic findings. While skin biopsies may show eosinophilic infiltration, phagocytic histiocytes, and often flame figures, diagnosis can be delayed by nondiagnostic samples. The experience of the pathologist and the quality of the sample are crucial. Flame figures are frequently present in this disease (50% to 96%) and often considered pathognomonic.1,2 Eosinophilia is not always present in the peripheral blood smears and occurred in only 50% of patients in one review.1 Leukocytosis is also particularly insensitive and may be present in only 40% of cases.2

(click for larger image)

Figure 2. (A) Punch biopsy of the left neck lesion with thickened stratum corneum and leukocytosis. (B) High powered field showing extensive eosinophilic infiltrate.

While a presentation similar to bacterial cellulitis is common, a significant degree of clinical polymorphism may further complicate diagnostic efforts. Recent studies have reported cutaneous variants with nodular, bullous, papulonodular, plaque-like, annular granuloma-like, and urticaria-like lesions. Based on this heterogeneity, one author suggested dividing eosinophilic cellulitis into distinct subtypes to better categorize the disease.1 This case of ulcerated, crusting, and fungating lesions with subdermal plaques further supports its variability and may showcase a novel presentation.1,2

Treatment involves systemic steroids and may include histamine blockers and topical anti-inflammatories, but the recurrence rate ranges from 56% to 100%.1-4 The natural course of the disease is also variable and may include a relapsing/remitting cycle, although some patients do experience remission even with appropriate treatment. The clinical progression depicted in this case report highlights how this disease process can mimic head and neck malignancy.

References

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Lunardon L. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Sinno H, Lacroix JP, Lee J, et al. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells’ syndrome): a case series and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20:91-97.

- Gandhi RK, Coloe J, Peters S, Zirwas M, Darabi K. Wells Syndrome (eosinophilic cellulitis): a clinical imitator of bacterial cellulitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:55-57.

- Weiss G, Shemer A, Confino Y, Kaplan B, Trau H. Wells’ syndrome: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:148-152.