During the 2017 Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting, held January 18–21 in New Orleans, a panel of experts in head and neck cancer discussed the ramifications of the rise in human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive oropharyngeal cancers. Discussion ranged from the value of HPV positivity in identifying unknown primary tumors to the increasing frequency of difficult family conversations after diagnosis of an HPV-positive cancer to issues that will be faced by more and more survivors.

Explore This Issue

April 2017Christine Gourin, MD, professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, said that HPV cancers are becoming so much more common that by 2030, it is projected that the most common head and neck mucosal cancer will be HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, while the incidence of head and neck cancers arising from other mucosal sites is actually declining. HPV tumors are associated with better survival, as well. “Traditional AJCC [American Joint Committee on Cancer] stage doesn’t seem to apply to that group,” Dr. Gourin said.

Human papillomavirus.

© Komsan Loonprom / shutterStock.com

David W. Eisele, MD, Andelot professor and director of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins, said that when an adult patient comes in with a solitary neck mass, it is “most likely” going to be cancer, usually squamous cell carcinoma. The earliest diagnostic step shouldn’t be an open-neck biopsy, he said. “Unfortunately, we continue to see patients come in with that procedure having been performed,” he added.

If a nodal metastasis is HPV-related, Dr. Eisele said, it reliably identifies the oropharynx as the site of the primary tumor, often small primaries with advanced nodal disease. HPV status also provides important prognostic information. Pinpointing the primary tumor site improves outcomes, he said.

A 2016 comparison of fine-needle aspiration specimens to resected nodes found that the sensitivity and specificity were “quite good” for linking HPV to the oropharyngeal or the unknown primary patient (J Clin Virol. 2016;85:22–26).

Dr. Eisele emphasized that the presence of p16 protein alone was not a direct marker of high-risk HPV because p16 can be elevated in ways that are not virus-related; histological, anatomic, clinical, and technical factors must be considered.

Dr. Eisele raised concern about proceeding with an initial combination palatine-lingual tonsillectomy approach to identifying the unknown primary, citing studies in which primary tumors were found in the palatine tonsils in many cases, making lingual tonsillectomy, which brings risks for morbidity, unnecessary. (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:1203–1211). Therefore, he said, a sequential approach may be the better choice. Further studies are needed to better define the optimal diagnostic pathway, he concluded.

Treatment De-Intensification

Michael Hinni, MD, an otorhinolaryngologist at the Mayo Clinic in Phoenix, said it’s becoming clear that de-intensifying treatment—using the same intensity of treatment but in a more focused way with less morbidity—is feasible in HPV head and neck oropharyngeal cancers.

He said that transoral surgery can be an advantage for more than just small tumors. The technique allows surgeons to remove the primary cancer in pieces so that it can be mapped and its margins more carefully monitored, with less normal tissue removed.

Patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal tumors, who traditionally have undergone radiation therapy after surgery, may not need it, he said. In one study of 69 patients who underwent transoral microsurgery alone, a third had an indication for radiotherapy but declined it, and only three of those patients had local recurrences (Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:1225–1230). “This speaks to our ability to effectively clear margins,” Dr. Hinni added. “De-intensification, in my mind, is adjusting the dose, adjusting the volume, or perhaps eliminating it altogether.”

A radiation oncologist at his center has finished Phase 2 of a study on patients with intermediate or low risk who, when they qualified for radiation, received just 30 Gy over the course of two weeks. Among 70 patients, there had been no local recurrences for more than two years. “Now, a larger study is following,” Dr. Hinni said. “This has the potential to be a game-changer.”

He added that limiting therapy, when possible, is even more attractive considering that surgery alone is a quarter of the cost of non-surgical treatment.

Prevalence

Marilene Wang, MD, professor of head and neck surgery at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Medicine, said that while it remains true that HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is associated with a higher number of sex partners, there’s no cause for shame or stigmatization. “It’s a very common infection, and many patients with this disease do not actually have a high-risk sexual history; more than half have fewer than five lifetime oral sex partners,” she said.

When a diagnosis of an HPV-related cancer is discovered, it’s important for physicians to let couples know that 80% of the population have been exposed to HPV and 7% have an active HPV infection. They should know that it’s not necessarily a sign of promiscuity, Dr. Wang said.

Patients and their partners should also know that exposure doesn’t mean you’ll develop cancer and that their sexual lives should continue; that they could consider protection with new partners; and that the rate of HPV infection among partners is actually the same as it is in the general population.

Caring for Survivors

Bruce Campbell, MD, chief of the division of head and neck oncology and a professor of otolaryngology and communication sciences at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Madison, said that with the prognosis of HPV cancer survivors so favorable, handling long-term issues will be critical in the future. “We are going to see many of these patients for years. This will be especially true for our younger colleagues and current residents,” he said. “This may be a pretty significant part of your practice.”

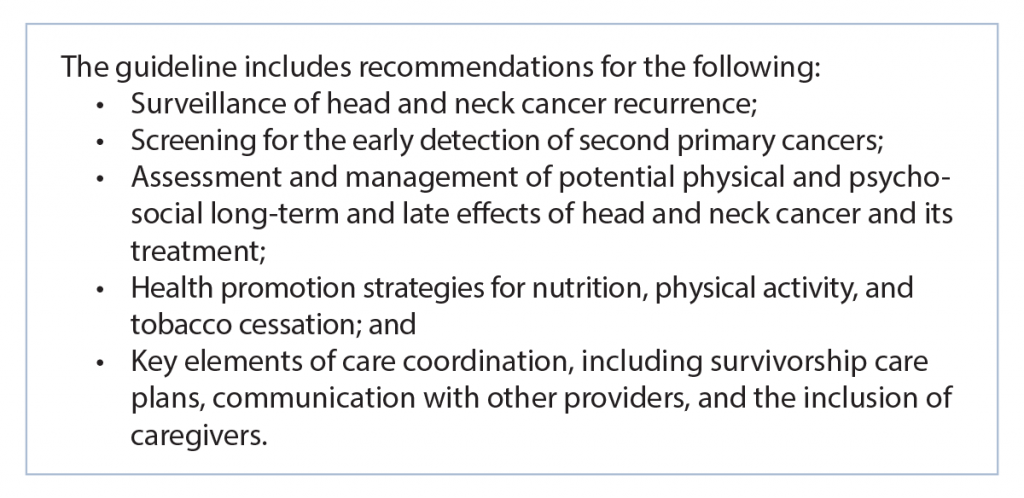

American Cancer Society guidelines, updated in 2016, cover surveillance, screening for second primary malignancies, assessing and managing physical and psychosocial long-term effects, promoting good health practices, and coordinating care among different providers (CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203–239) (See American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline).

(click for larger image) American Cancer Society Head and Neck Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline (2016).

Source: CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203-239.

Surveillance visits suggested by the guidelines include a checklist of nearly 30 items, which is not feasible for many providers, but Dr. Campbell emphasized the most practical considerations. “How do these people return to work? How do we help them become functional again?”

Giving out “survivorship care plans” that include a summary of staging and treatment, though, did not work very well in a small study with a three-year follow-up. Most patients didn’t have the pamphlets or even remember ever getting one. “We need to find better ways to get that information to our patients,” Dr. Campbell said.

He added that follow-up visits rarely find a new cancer and that physicians need a new understanding of the goals of long-term surveillance. The main issues are more subtle. “We need to listen to their stories,” he said, “and understand that there are a lot of other issues to which you and I as their care providers need to be attentive.”

Thomas Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

Take-Home Points

- HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer is projected to become the most common head and neck cancer by 2030.

- An HPV-positive finding can help identify the site of unknown primary tumors and guide treatment.

- De-intensifying both surgical and radiation treatment can be effective in some patients.

- Patients and their partners should know that an HPV-positive diagnosis is not necessarily a sign of sexual promiscuity or unfaithfulness.

- Survivorship issues, including life function and psychosocial problems, are becoming more and more important as patients with HPV-positive cancers live longer.