The health care reform law passed in March created a $50 million demonstration program to test alternatives to the current medical liability system. But reaction is mixed as to whether the new project will help fix what the physician and medical liability insurance communities view as a flawed and inefficient system.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act authorizes the Department of Health and Human Services to award grants to states to develop, implement and evaluate different approaches to tort litigation. The projects must improve the availability of prompt and fair dispute resolution, encourage disclosure of medical errors, enhance patient safety and improve access to liability insurance.

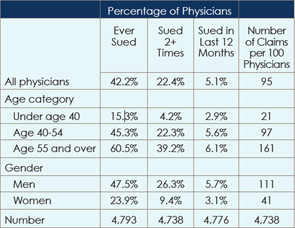

American Medical Association (AMA) survey findings released in August indicate that, on average, 95 medical liability claims are filed for every 100 physicians. However, about 65 percent of claims against physicians are dropped, dismissed or withdrawn without payment, according to data from the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA). Physicians are found not negligent in more than 90 percent of the cases that do go to trial, and about $120,000 is spent defending those claims.

“The new grants alone will not change the medical liability climate in our nation overnight, but they may plant seeds that could have a long-term, positive impact,” said J. James Rohack, MD, AMA immediate past president. They are no substitute for caps on noneconomic damage awards, which have proven successful in California and Texas, he said. They could complement damage limits, however.

States Present Ideas

The demonstration program is an indication that Democrats, who generally oppose noneconomic damage caps, see a need to address the system’s problems with medical liability, experts said. In a separate effort, in June 2010, the Obama administration issued similar grants as part of its medical liability reform and patient safety initiative.

If the June grants are any indication, the new project won’t focus primarily on reforming the tort system, said Lawrence E. Smarr, PIAA president. All but one of the seven demonstration grants, worth $19.7 million, emphasize patient safety, he said. “It’s a good idea to be focusing on patient safety, but that’s not tort reform,” he added.

Only a nearly $3 million grant to New York state to test a judge-directed negotiation program in cases involving obstetrical and surgical injuries qualifies as tort reform, Smarr said.

In June, in addition to the nearly $20 million in demonstration grants, the government announced $3.5 million in planning grants to fund development of medical liability reform projects. These initiatives could be candidates for the health reform law’s demonstration program, said Michelle M. Mello, JD, PhD, professor of law and public health at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.

One idea that received a planning grant involved the creation of a list of “avoidable classes of events,” followed by cooperation with liability insurers, who would offer a standard amount of compensation to patients harmed in such incidents. The model, being developed in Washington state, also involves identifying avoidable patient safety problems and providing an acknowledgement and an apology when an event occurs. The idea is that a prompt apology and compensation would deter litigation.

Another effort given a planning grant in June that could be a candidate for the reform law program is a test of liability safe harbors, Dr. Mello said. The project, initiated in Oregon, entails development of legislation that would use practice guidelines to define the legal standard of care. The legislation would also include a plan to evaluate its effectiveness.

“The idea here is if you have a doctor who has complied with a best practice guideline that some trusted body has deemed representing good practice, and if he’s later sued out of an incident or harm arising from that care, he should be able to use the practice guideline as a defense,” Dr. Mello said.

The American College of Surgeons supports this concept, said its president, L.D. Britt, MD, who added that safe harbors are “ready for primetime.”

A big thrust of the health reform law is to get doctors to use evidence-based research. The safe harbor concept is “a way to provide a concrete financial incentive to push them in that direction,” Dr. Mello said. Some issues that need to be worked out are how to select the guidelines among the many sets that exist and how to make that process transparent and defensible so that plaintiffs’ attorneys don’t criticize them as self-serving standards created by doctors, she said.

Two other demonstration grants and a planning grant involve the idea of early disclosure and compensation. Under this model, the defendant would quickly disclose the error and offer to pay damages and reasonable attorney’s fees within a set time frame. The plaintiff would agree to forego further recourse in court.

Health courts are another idea with a lot of buzz. Under this concept, championed by the nonprofit legal reform coalition Common Good, medical injury cases would go to specialized courts featuring adjudicators with medical expertise, independent expert witnesses and predictable damage awards.

“The changed state political landscape may not improve the chances for award caps.”—Michelle M. Mello, JD, PhD

“The changed state political landscape may not improve the chances for award caps.”—Michelle M. Mello, JD, PhDStipulations in the health reform law, however, could make a health court project an awkward fit for the program. The law states that the demonstration projects cannot limit patients’ existing legal rights or ability to file a claim in state court and that patients may opt out of a project at any time and file under the existing system. So, for example, a liability insurer “could decide to convene a health court-like panel, but ultimately patients can opt out of that at any time even if they go all the way through the process,” Dr. Mello said. “Obviously, that limitation in the health reform law significantly restricts the kinds of experiments that we could see under these demonstrations.”

The stipulations are a fundamental flaw in the law, Smarr said. “What good is it if [when plaintiffs] don’t like the way it’s going, [they] can leave?”

The Future of Caps

The PIAA, AMA and American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) have vowed to continue to push for tort reforms like those passed in California and Texas, both of which cap noneconomic damage awards at $250,000. The Republican takeover of the U.S. House in the November 2010 elections improves the chances for passage of similar reforms in that chamber next year, experts interviewed for this article said. The Senate, which remains majority Democrat, is expected to block any such effort.

GOP gains at the state level mean tort reform with noneconomic damage caps could become a hot topic at the state level. At the gubernatorial level, several states flipped to the GOP, bringing the total number of Republican governors to at least 29. The party also gained control of one or both houses in 13 state legislatures. The changed state political landscape may not improve the chances for award caps, Dr. Mello said. Because of court setbacks in some states, politicians might not want to expend political capital on the issue, she explained. Earlier this year, the Georgia and Illinois Supreme courts struck down noneconomic damage caps.

The medical community must keep fighting at the federal and state levels for medical malpractice reforms like those in California and Texas, said Ronald B. Kuppersmith, MD, AAO-HNS immediate past president. “You have to keep trying because you never know,” he added.

Leave a Reply