Clinical Scenario

You are the program director of a mid-sized otolaryngology residency program. You feel it is important to keep a close eye on all aspects of residency training, especially the welfare of the residents and their patients. You have regular formal discussions with each of the residents about their progress, as well as infrequent, more personal discussions designed to listen to their thoughts and comments.

Explore This Issue

April 2017You find yourself increasingly concerned about the welfare of two of your residents—one a PGY-2 and the other a PGY-4. To different degrees, both of these young professionals are exhibiting subtle, but clear, changes in their personalities and work, including distancing themselves from their colleagues and faculty, showing signs of emotional exhaustion and physical tiredness, and exhibiting some lapses in the quality of their patient care.

When you bring up this issue at the next closed faculty meeting, you find that other faculty members have noticed the changes, but they express the opinion that perhaps the two residents are just going through a “phase.” Believing it may be more significant and serious than that, you plan to research the issue of burnout in residency training, especially for otolaryngology residents, before you develop a plan for discussing the collective faculty concerns with each of them.

How would you handle this case?

Discussion

© Yeexin Richelle / shutterStock.com

Over the past 15 years, physician burnout has become an increasingly recognized entity in the profession, with a growing literature base to reflect its importance. In a survey of surgeons, the American College of Surgeons identified, among the 7,905 respondents, a 40% burnout rate, a 30% positive screen for symptoms of depression, and a mental quality of life score one-half standard deviation below the population norm (Ann Surg. 2009;250:463–471). Numerous studies have confirmed this range of burnout over many specialties, both medical and surgical. Burnout occurs in both community practitioners and academic faculty alike, and it occurs in military physicians working in a high tempo combat deployment environment. Concerns about the effects of this level of physician burnout on patient care are clearly appropriate.

Burnout in physicians and surgeons is a response to multiple factors that can negatively impact their professional and personal lives, leading to emotional exhaustion/depletion, depersonalization, reduction in career satisfaction, and negative patient and non-patient personal interactions. Burnout may be a progressive process that waxes and wanes over the years, depending on the work and personal environments, but it may eventually lead physicians and surgeons to consider early retirement or a career change away from direct patient care. Quality-of-life issues with respect to work-personal balance can be caused by burnout as well as affected by this condition. In sum, burnout has come to the forefront as a major professional issue that needs to be recognized, understood, and mitigated.

Younger physicians and surgeons may be more susceptible to developing burnout, perhaps in part because they have not yet developed appropriate experience and coping mechanisms. Indeed, it is estimated that up to 50% of medical students exhibit signs or symptoms of burnout at some point in their undergraduate medical career (Bull Am Coll Surg. 2011;96:17–22). This may well carry into residency training, and might even be exacerbated by increased educational and clinical pressures and decreased personal recovery time. Residency training is a time of highly accelerated acquisition of knowledge and skills and includes challenges in time management and wide-ranging experiences. Particularly in the surgical specialties, each resident physician brings to the training experience an abundance of intellectual and technical skills, cultural and family experiences, biases and perspectives, and personality traits. For surgeons, a healthy dose of obsessive/compulsive behavior is felt to be necessary, with perfectionism often a goal, even when these behaviors can occasionally reap negative results.

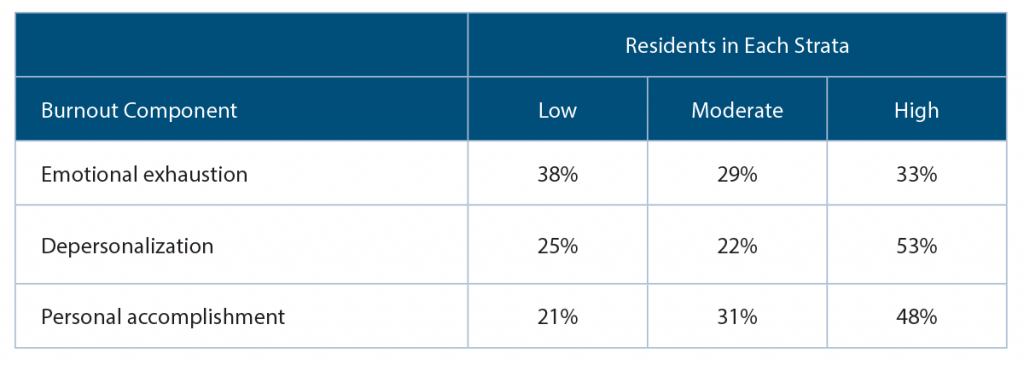

One of the best studies performed to date on burnout in otolaryngology residents was a survey published in 2007 by Golub and colleagues (Acad Med. 2007;82:596–601). The survey results were based on the responses of 514 otolaryngology residents in the second through fifth years of training. The authors reported an 86% response rate for residents reporting moderate (76%) or high (10%) levels of burnout at some time during their residencies (See “Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Study Subscale Stratification of Otolaryngology Residents,” below). Interestingly, high levels of personal accomplishment seemed to buffer or protect against burnout.

If emotional exhaustion is an early predictor for the development of some level of burnout, it seems reasonable that close observation of a resident physician for this phenomenon would be a salutary finding to prompt intervention and mitigation. When depersonalization of oneself and of the patient leads to diminished capacity for self-realization and concern for the patient, burnout is at a serious stage. What follows may be an obvious lack of concern for personal appearance and care, and for the care of and interaction with patients. Errors and mishaps in patient encounters may occur, and these may further depress the resident, leading to lowered feelings of self-worth and a downward spiral of competency. Bedside manner becomes worrisome.

(click for larger image) Maslach Burnout Inventory–Human Services Study Subscale Stratification of Otolaryngology Residents

n=514

Source: Acad Med. 2007;82:596–601.

Early Recognition

It is an ethical imperative for the program director—as well as all faculty members—to be aware of the burnout phenomenon, and to always be observant for signs of its occurrence. Better yet, programs need to institute, or strengthen, preventive programs that directly impact and mitigate the issues that can lead to burnout in residency. This may well begin with faculty training on the burnout phenomenon, both for their own welfare and to enable them to recognize the signs and symptoms (perhaps in themselves as well as in the residents). Faculty recognition of the insidiousness of professional burnout will provide a better sense of why it is important to prevent and/or ensure early mitigation of these representative personal difficulties—physical and emotional exhaustion, detachment from social interactions, poor patient communications, difficulties with personal relationships, decreased self-confidence and self-worth, mistakes in patient care, and signs of clinical depression, to name a few.

Residency programs that are successful in addressing burnout in residents have become proactive with respect to surveillance, recognition, prevention, mitigation, reassessment, and ongoing monitoring. These programs have also put into place a wide range of strategies that prepare residents for the challenges and disappointments that characterize a surgical career, while emphasizing the benefits and joys of being a caring, compassionate, and competent otolaryngologist. Teaching coping mechanisms for stress, emphasizing proper diet and exercise, facilitating appropriate rest time and vacations away from training, promoting faculty-resident mentoring programs that allow for discussions and encouragement, and offering the opportunity to take advantage of mental and physical wellness programs provided by the academic institution will all be salutary methodologies.

While early recognition of the signs of resident burnout is a prerequisite for mitigation, perhaps the most important effort is to prevent it, if possible, or at least to reduce its risk in a residency training program. Effective prevention or mitigation seems to involve two major elements—systems/environmental control and attention to the person. Regarding the former, many education programs on physician burnout are available, and these are excellent awareness tools for both residents and faculty—viewed and discussed as a group. Residency training is clearly not too early to learn about this issue, which may affect over 40% of practicing otolaryngologists to varying degrees during their clinical lifetime. Resident work hours are monitored for a reason—to prevent exhaustion and cognitive deterioration. A training program is responsible for monitoring the workload of residents and making changes if a systemic problem is identified.

Addressing the personal progress and status of individual residents has been one responsibility of training programs and faculty for many decades. We know that each resident brings a spectrum of personal attributes, technical and efficiency capabilities, learning styles, and yes, weaknesses, to a training program. Individual support for residents can be based, in part, on their personal capabilities, emphasizing their strengths and minimizing their weaknesses, in the context of excellent patient care and professionalism. Faculty role modeling and mentoring with respect to work/life balance, stress management strategies, personal diet and exercise, interpersonal relationship building, importance of family and friends, and ways to enhance the virtues of a physician all play a role in preventing burnout.

Resident physicians in surgical specialties have unique stressors that are different from those in medical specialties—namely, the potential risks and complications that can occur with surgical procedures. When complications occur—and they will—young physicians can be devastated by them. Faculty and/or professional counseling, including post-surgical procedure debriefing and family interaction, can guide them through the emotional trauma while helping them to learn from the events.

So, what are the ethical considerations of burnout in resident physicians? The negative aspects of burnout can adversely affect patient care, effective learning, personal health, and interpersonal relationships. Burnout in a resident, if not addressed and mitigated, can persist into practice, becoming a problem for both patient and physician. The burned-out otolaryngologist is unhappy and depressed, and spreads those feelings to those around him/her, especially to the patient. It is our ethical responsibility to address this issue and discharge our duty to patient, physician, profession, and society.

Dr. Holt is professor emeritus in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

Key Points

- Physician burnout has become an increasingly recognized issue in the profession.

- Younger physicians and surgeons may be more susceptible to developing burnout.

- It is an ethical imperative for the program director and faculty members to be aware of the phenomenon.