LAS VEGAS—The question seemed simple. Which medications was a patient at the Pittsburgh VA taking?

When a veteran patient with advanced head and neck cancer took a look at a list that was brought up on a computer, a list thought to be comprehensive, he had some news for his physician: He was on a lot more medication than that.

A nurse knew where to go in the system to find the rest of his medications, which were purchased outside of the Veterans Affairs system, but it was a few non-intuitive keystrokes away.

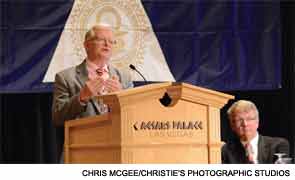

“How could this be? How could something so simple as generating a medication list be so difficult?” asked David Eibling, MD, professor of otolaryngology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, as he delivered the Joseph H. Ogura Lecture at the 117th Annual Meeting of the Triological Society, held as part of the Combined Otolaryngology Spring Meetings.

The example could be chalked up to defective software: Although the non-VA medications had been placed on the patient’s list—part of his medical record—the list was not easily viewable by physicians at a different VA hospital.

But actually, the problem was a systems mistake, Dr. Eibling said. When a veteran gets medications from outside of the Veterans Affairs system, those other medications are listed somewhere else, and only if somebody enters them manually. Moreover, the reason the patient was getting his medications from Wal-Mart in the first place pointed to another system flaw nested inside the first system flaw: It was significantly cheaper to do so.

When physicians want to go about trying to make improvements, Dr. Eibling said, the best course is to target the system in which they’re functioning. Is the system designed to accomplish what it’s meant to accomplish? “It’s not difficult to recognize a problem when it’s acute and our patients are injured,” he said. “But as we drill down in acute system injury, we often find that there’s chronic illness or perhaps even congenital illnesses. This system that’s sick has oftentimes been sick for some time.”

There is an urgency, he said. “If nothing changes, we can expect that one in 20 of us in this room will die or be seriously injured by a medical error,” he said.

The Challenge

Seeing the sickness of systems might be more difficult to do than it seems. Dr. Eibling likened healthcare professionals and their healthcare systems to a goldfish staring out at its surroundings—it might be easier to see what’s far away than to see the water you’re swimming in every day.

People also tend to fall prey to “hindsight bias,” a tendency to attribute causation to the individual we see as responsible after an outcome is known, he said. “This type of cognitive bias is related to the cognitive biases that impair our ability to make diagnoses of patients,” Dr. Eibling said.

The good news, he said, is that physicians have a lot of characteristics that should enhance their ability to try to solve these systems issues. They have a desire to do good for others and a respect for science, seeking out evidence when it isn’t readily available.

At VA Pittsburgh, for example, a color-coding system, the success of which has been supported by evidence from the anesthesia literature, has been adopted in the operating room as a way to prevent back table medication errors, he said. (There were no errors previously, and none have occurred since the new system was put in place, he said.)

“What I’d like to do is encourage you to take an active role in diagnosing and improving systems in your environment,” Dr. Eibling said. A key part of that, he said, is to seek out expertise from other areas and learn the “language” of these systems. “You’re going to find that in schools of business, psychology, and engineering,” he said, “they’ll be very eager to help you in your work to heal systems.”

As educated professionals, physicians have an opportunity to educate others, he said. “I would suggest that one of the ways we can change systems is by educating—particularly leadership—in the principles of system design, system diagnosis, and how to change systems,” he added.

He cautioned, though, against a potential backlash or being seen as a “troublemaker” if you don’t use the right approach. He encouraged the audience to familiarize themselves with “appreciative inquiry,” a way to ask questions and promote change that builds on imagination and strengths, rather than relying on criticism.

“Once you start trying to heal systems, it becomes a little addicting,” he said. “Don’t do what I do and try to fix everything. Pick one or two [problems] and focus on them.”

Leave a Reply