INTRODUCTION

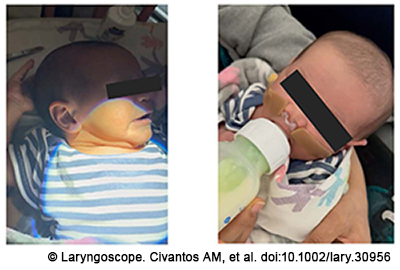

Figure 1. Two-week-old male with midface/maxillofacial hypoplasia with improvement in feeding and work of breathing after 10 days of nostril retainer use.

Nasal septal deformity (NSD) of the newborn can range from isolated anterior caudal septal deflection to subluxation of the septum off of the maxillary crest with significant deviation and gross external nasal deformity. The overall incidence varies in the literature from 1.9% to 22%, likely as a result of inconsistent diagnostic criteria among the studies (Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0808-4). The presentation of the newborn can range from asymptomatic to significant respiratory distress and feeding difficulties, depending on the degree of obstruction. Confirmation can be made by assessment of the external nasal appearance, anterior rhinoscopy and, if necessary, nasal endoscopy.

The etiology of the condition is debated by authors, with some suggesting trauma during decent in the birth canal or during delivery and others favoring intrauterine trauma. Debate in the literature also exists as to the significance of primiparity, delivery method, fetal weight, and duration of labor in the etiology of newborn nasal septal deformity (Clin Pediatr. 1974. doi:10.1177/000992287401301107).

No clear treatment algorithm exists for the management of newborns with NSD. Arguments exist both for careful observation with nasal reduction only in the setting of respiratory distress or early intervention with closed reduction. Those in favor of early reduction note the relative ease and low morbidity of the procedure, the ability to perform it at bedside without anesthesia, the risk of persistent nasal deformity in absence of correction, the potential consequences nasal deformity may have on mid-face development, and the potential for increase in upper respiratory tract infections in children with nasal obstruction. Furthermore, newborns are obligate nasal breathers for the first three months of life, so any compromise of the nasal airway could potentially lead to respiratory distress and/or associated feeding and growth issues. Those who argue for observation in the absence of respiratory compromise note that the nasal deformity often spontaneously resolves with time (Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009. doi:10.1007/s00405-008-0808-4; Clin Pediatr. 1974. doi:10.1177/000992287401301107).

We present a case of a newborn born with an NSD that was treated with placement of a nostril retainer to reduce the septum and secure it in place in the neutral position. This represents a novel indication for use of a nostril retainer in addition to reduction alone for potential improved outcomes in infants presenting with postnatal NSD or nasal obstruction causing feeding issues. We have subsequently used this technique for another infant who also sustained nasal trauma during delivery and a third infant with nasal obstruction leading to poor feeding.

METHOD

A one-day-old female born at 40 and 6/7 weeks to a healthy 23-year-old G1P0 mother was noted at birth to have an external nasal deviation to the left. Birth was complicated by prolonged labor with a vacuum-assisted delivery. The patient was not reported to have any respiratory distress, noisy breathing, or feeding difficulties upon questioning of the parents and nursery team. The exam was notable for anterior fontanelle edema with an ecchymotic strip across the superior forehead, ptosis of the nasal tip, and severe deviation of the middle and lower nasal vaults to the left. Anterior rhinoscopy revealed severe, leftward, anterior septal deviation with a marginal left nasal airway. Palpation of the nasal bones revealed they were intact with no evidence of fracture. No other abnormal findings were noted on a complete head and neck examination.

A size 1 Porex nostril retainer was placed into both nasal cavities and the nasal pyramid was repositioned in a more neutral position. The Porex nostril retainers range from sizes 1 through 13 with gradually increasing columellar band distance, length of the individual nostril tubes, and outer diameter of the nostril tubes. Nostril retainers have historically been used after cleft lip repairs to maintain nasal architecture. At our institution, sizes 1 through 3 are stocked for pediatric use. Informed consent was obtained from the parents.

The pediatric nursery staff and primary pediatric team were present at the bedside during the procedure. The baby was given oral sucrose during the procedure to provide pain relief. The outer surfaces of the nostril retainer were lightly coated in bacitracin ointment with care taken not to obstruct the lumens of the nostril tubes. The nasal pyramid and septum were gently repositioned in the midline and the nostril retainer was atraumatically inserted in a direction parallel to the nasal floor. With the nose positioned in as neutral a position and the nostril retainer in place, the side tabs were secured to the facial soft tissue with steri-strips, both to secure the nostril retainer and maintain the neutral position of the nose.

This technique has subsequently been used for two other infants. A 10-day-old male born at 35 and 6/7 weeks with a similar nasal deformity from delivery for which a size 1 Porex nostril retainer was placed atraumatically. The ends of the retainer were trimmed to optimize positioning in the nasal airway. Finally, a size 1 Porex nostril retainer was also used for a two-week-old male born at 39 weeks with midface/maxillofacial hypoplasia who was noted to have feeding difficulties due to bilateral nasal stenosis. In these two cases, a nasal cannula adhesive strip was used to secure the retainer in place.

Of note, in the three cases presented, the size 1 nostril retainer was easily placed without resistance. We would caution providers to not proceed if meeting resistance with the smallest size retainer to avoid any risk of necrosis.

RESULTS

Significant improvement in nasal position was noted, even after three days. The patient was discharged home with the retainer in position and parents instructed on how to remove, replace, and secure if it became dislodged or appeared to be contributing to any breathing difficulties. Follow-up was scheduled in the pediatric otolaryngology clinic one week later. The parents reported no breathing or feeding difficulties over the intervening time period. The nasal pyramid had remained in a neutral position and the septum was noted to be midline. The nasal retainer was removed without difficulty.

For the second case, the nostril retainer fell out on its own after two to three days and was not replaced at home due to satisfaction with the appearance of the nose at the time.

For the third case, placement of the retainer resulted in immediate improvement in work of breathing and feeding (Figure 1). It was replaced one to two times a day by the parents for about 10 days, and then transitioned to nighttime use.