Each virtual procedure tried on the CM platform should produce an expected patient improvement level. Dr. Frank-Ito thinks this will lead to personalized and optimal surgical treatment for patients.

Explore This Issue

May 2017

With further development, more advanced tools could be developed, providing real-time guidance for physicians and, hopefully, making surgery easier and more successful. —Jason Lu, PhD

Predicting Patient-Specific Outcomes

Another possible use of CM is to predict individual postoperative complication rates. One such program looked at forecasting adverse outcomes following oral cavity cancer surgery.

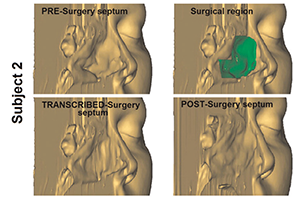

Figure 2. 3D transcribed-surgery model of the nasal septum.

“Head and neck cancers are complex, particularly in the surgical management,” said Mahmoud I. Awad, MD, resident physician in the head and neck service of the department of surgery at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. “We find it is very difficult to predict postoperative complications and physicians often just use their clinical judgment.” This can be frustrating, added Dr. Awad. So, he and his colleagues set out to develop nomograms to better quantify this risk, and to be able to relay the risk to patients during presurgical counseling (JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:960–968).

The researchers retrospectively reviewed the charts of 506 patients treated surgically for primary oral cavity squamous cell cancer at their institution. One cohort was used to develop nomograms examining 36 potential complication predictors and to determine which were statistically more likely to predict complications. From this information, the group then constructed the nomograms. The other cohort was used to validate the nomograms once they were designed.

Clinical characteristics were similar between the groups for most comparisons. The six preoperative variables with the highest individual predictive values were incorporated into the nomograms. The nomogram predicted major complications with a validated concordance index of 0.79. When they added surgical operative values, predictive accuracy was maintained at 0.77.

“What is great about nomograms is that they are a combination of being user friendly and allowing us to personalize medicine,” said Dr. Awad. “All the variables entered into consideration are specific to the individual in front of you. In theory, the information you are giving them on risk is specific to that individual patient. It is a very powerful tool.”

Dr. Awad is confident that this method has the possibility to change practice significantly. The clinician should be able to enter variables into a computer in real time and get results to share with the patient immediately. In addition, being able to assign a specific risk to a patient could have implications in other areas of healthcare, such as allocation of intensive care unit beds and risk adjustment to normalize outcomes among different facilities for quality and pay-for-performance purposes.

We hope that eventually, [CM] will become a way for the surgeon to meld radiologic and other studies into a platform that lets them virtually plan and even practice long before they enter the nose. —Dennis O. Frank-Ito, PhD

Assessing CI Success

One concern physicians have about the use of cochlear implants (CI) in prelingual infants and toddlers is the difficulty of predicting the development of effective language skills in the first two years following surgery. Researchers from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and the University of Cincinnati developed a computer-based machine learning model to try to address this issue (Brain Behav. 2015 Oct 12;5:e00391. doi: 10.1002/brb3.391).