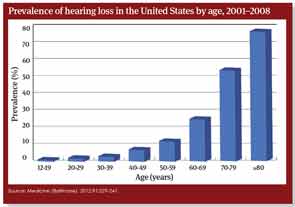

A generation ago, hearing aids were the treatment of choice for age-related hearing loss. Today, there is increasing recognition that cochlear implants can not only help older adults regain their hearing, but can also allow them to fully participate in life. According to a 2012 article in Medicine, the number of adults aged 60 and older who have received a cochlear implant at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore has increased annually over the last decade. Nearly 60 percent of those adults were over age 70; the oldest was nearly 95 (2012;91:229-241).

Other institutions report similar increases, but awareness of cochlear implantation as a treatment for age-related hearing loss is still lacking in both the general public and some segments of health care, and that lack of awareness may be unnecessarily inhibiting the health of scores of older adults.

“If we look at ballpark numbers, only about 5 percent of older adults who qualify for cochlear implants are getting them,” said Frank Lin, MD, PhD, assistant professor of otology, neurotology and skull base surgery at Johns Hopkins. Too many people, Dr. Lin said, mistakenly think that presbycusis isn’t a particularly harmful effect of aging. “They think, if age-related hearing loss is so common, how can it be so important? I compare it to blood pressure,” Dr. Lin said. “Twenty years ago, the accepted norm was 140 plus your age for systolic blood pressure; if it was below that, it wasn’t treated. So, if you were a 70-year-old man back in 1991 and your systolic blood pressure was 210, it wasn’t treated because back then, the attitude was that hypertension was something we all get as we age. Then the SHEP [Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program] study came out and proved that if you treat hypertension in older adults, you drop the rates of heart attacks and strokes. “The SHEP study demonstrated that just because something is common and a normal part of aging, it doesn’t mean it’s not without consequences,” he added.

Presbycusis is linked to a host of psychosocial and physical maladies, including depression, social isolation and dementia, and research strongly suggests that untreated age-related hearing loss may quicken physical decline (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1936-1945). Treating presbycusis with cochlear implantation can drastically improve older adults’ quality of life—and may improve their overall health as well.

Determining the Right Time

Although Medicare currently covers cochlear implantation when a patient’s Hearing in Noise Test (HINT) score drops below 40 percent with best-possible amplification, many patients and physicians don’t consider cochlear implantation until a patient is “stone cold deaf,” Dr. Lin said. That may be a mistake, because the available evidence consistently shows that older adults do better when they are implanted early.

According to a 2013 study, patients older than age 80 fare more poorly on speech perception tests after cochlear implantation than do patients aged 60 to 69 (Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1952-1956). Research suggests that this difference may be due, at least in part, to age-related changes in central auditory processing. A study of forward masking in elderly cochlear implant users found that older patients experienced significantly slower psychophysical recovery than younger implant users, despite the fact that both groups had similar auditory nerve recovery times after electrical stimulation (Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:355-363).

“The evidence argues for earlier implantation, as soon as candidacy criteria are met, because at that point, the brain is more capable of interpreting the new auditory signals,” said David Friedland, MD, PhD, professor and vice chair of otolaryngology and communication sciences at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. “Patients with better residual hearing at the time of implantation do better post-implantation.”

Bruce Gantz, MD, head of the department of otolaryngology at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, uses a common sense rule for determining initial eligibility for cochlear implantation: “My bottom line is that if an adult can’t communicate effectively on a telephone with hearing aids, it’s time to start thinking about an implant,” he said.

“When someone does not understand even 50 percent of a conversation without using visual cues, they miss a lot of information. There is an increased liklihood of becoming socially isolated and having more fatigue at the end of the day, as understanding speech becomes a mentally challenging task. There’s a higher tendency for depression,” said Ronna Hertzano, MD, PhD, assistant professor of otorhinolaryngology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. “When someone reaches that point, there is no reason to wait another five or 10 years, because things will only get worse.”

Earlier May Be Even Better

Unfortunately, the current Medicare guidelines leave out a lot of adults who could benefit from cochlear implantation. “By FDA criteria, we typically say people are candidates for cochlear

implantation when their HINT score is below 60 percent. So, the conundrum we face in our clinic is people who are 65 years old or so, with speech scores around 58 percent and a lot of trouble functioning,” Dr. Lin said. “Do we tell them, ‘Well, you qualify for cochlear implants, but by Medicare criteria, you don’t, so come back in several years?’ If they come back five or 10 years later, they probably won’t do as well as if they had been implanted earlier. We’re losing out on that five-to-10 year window when people could really benefit from cochlear implantation.”

A 2009 study of the cost-effectiveness of cochlear implantation in older adults noted that “greater benefits are found with earlier implantation and shorter duration of deafness prior to implantation” (Health Tech Assess. 2009;13:1-330).

“There is a direct correlation between the length of time from loss of benefits from amplification and intervention with cochlear implantation and the ultimate outcome,” Dr. Hertzano said. If cochlear implantation must wait, maintaining best-possible amplification with hearing aids will not only improve interim quality of life, but also increase the chances of good hearing outcomes after eventual implantation.

Restoring hearing sooner rather than later through cochlear implantation may preserve central auditory function. “With more prolonged periods of hearing loss, you literally can see atrophy in parts of the brain that handle speech processing,” Dr. Lin said. Earlier cochlear implantation may delay brain atrophy and increase the levels of hearing older adults are able to obtain from cochlear implantation.

Source: Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91:229-241.

Unilateral or Bilateral Cochlear Implants?

At present, unilateral cochlear implantation is far more common in older adults than bilateral implantation. The preference for unilateral implants is related to concerns about the ability of older adults to tolerate surgery, uncertain insurance coverage for bilateral implants and questions regarding the cost-effectiveness of unilateral versus bilateral cochlear implants.

“For older adults, we almost always start with unilateral implantation,” Dr. Lin said. “Then, depending on how the patient does six months to a year later, if they feel like they need a second one because the other ear really isn’t hearing anymore, we would consider a bilateral. We don’t really ever do simultaneous bilateral implantation, because most older adults do just fine with one. Simultaneous bilateral implantation doubles the surgery length, and reimbursement can get very, very tricky.”

In the future, bilateral cochlear implantation in older adults may be more common. A 2013 study found that bilateral implantation improves speech perception in noisy environments, and helps adults accurately localize sounds. Bilateral implantation also provides a backup system should one implant fail, even temporarily. However, the cost-effectiveness of bilateral implantation over unilateral implantation has not been established (Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:190-198).

Post-Implant Life

Most older adults tolerate cochlear implantation surgery and the subsequent rehabilitation extremely well; however, careful pre-operative selection and teaching can increase the chances of patient satisfaction after implantation and activation.

For most post-lingually deafened adults, adjusting to life with a cochlear implant is “like riding a bike,” said Robert Labadie, MD, PhD, professor of otolaryngology and biomedical engineering at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. But “some patients may not like it,” Dr. Gantz said. “They may be disappointed that it doesn’t generate the information they thought it would immediately; sometimes it takes time, and there’s variability of performance. Not everybody gets to 80 or 90 percent word understanding.”

Additionally, some studies have suggested that older adults, especially those older than age 75, are more likely to experience balance problems post-cochlear implantation than younger adults (Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:1272-1277). Preparing patients (and families) for the possibility of balance difficulties after surgery may increase patient safety and satisfaction. “We need to counsel patients and let them know that if they are having balance problems before surgery, they may have more after,” Dr. Labadie said. “We want them to be aware so they can take appropriate measures and not put themselves in unsafe settings.”

In the years to come, cochlear implantation of older adults is predicted to increase. “We are literally at the tip of the iceberg in terms of the crush of older adults who are aging but very healthy and want to live to their full potentials,” Dr. Lin says. “I think there’s going to be a huge increase in the number of patients who will qualify and who are likely to want a cochlear implant.”

Leave a Reply