© Arthimedes / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM

A lot has changed since the first cochlear implant was performed more than 30 years ago. Successful in a wide range of patients, including the elderly, cochlear implantation is now the standard of care for treatment of severe to profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. And recent improvements in technology have made cochlear implants accessible to a new set of deserving patients—those with some residual hearing.

Explore This Issue

November 2017Cochlear implant candidacy has evolved dramatically since multichannel implants were first approved in 1985 for adults and in 1990 for the pediatric population. “Previously, individuals were required to have a profound sensorineural hearing loss in both ears—that is, minimal to no speech recognition—in order to be considered a candidate for cochlear implantation,” said Erin Blackburn, AuD, MS, co-director of the cochlear implant program at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, N.C. Over the past five to 10 years, the candidacy criteria have become less rigid and now include individuals with more residual hearing, Dr. Blackburn said.

“Now that we know that cochlear implants work and that the outcome is reliable for the vast majority of people, we are implanting people with moderate to profound hearing loss, not just profound hearing loss,” said Anil K. Lalwani, MD, professor and vice chair for research, director of the division of otology, neurology, and skull base surgery, and director of the Columbia Cochlear Implantation Program at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City.

This is especially important for the aging population. “As we get older, we lose clarity of hearing. So, while the elderly can still hear sounds, the words are not clear. In more severe cases, they understand fewer than four out of 10 words in a sentence,” Dr. Lalwani said. “While a well-fitted hearing aid is excellent at enhancing signal-to-noise ratio, it can’t improve clarity. The cochlear implant is able to bypass the dead hair cells in the inner ear and stimulate the auditory nerve directly, thereby restoring clarity.”

Current Criteria and Controversy

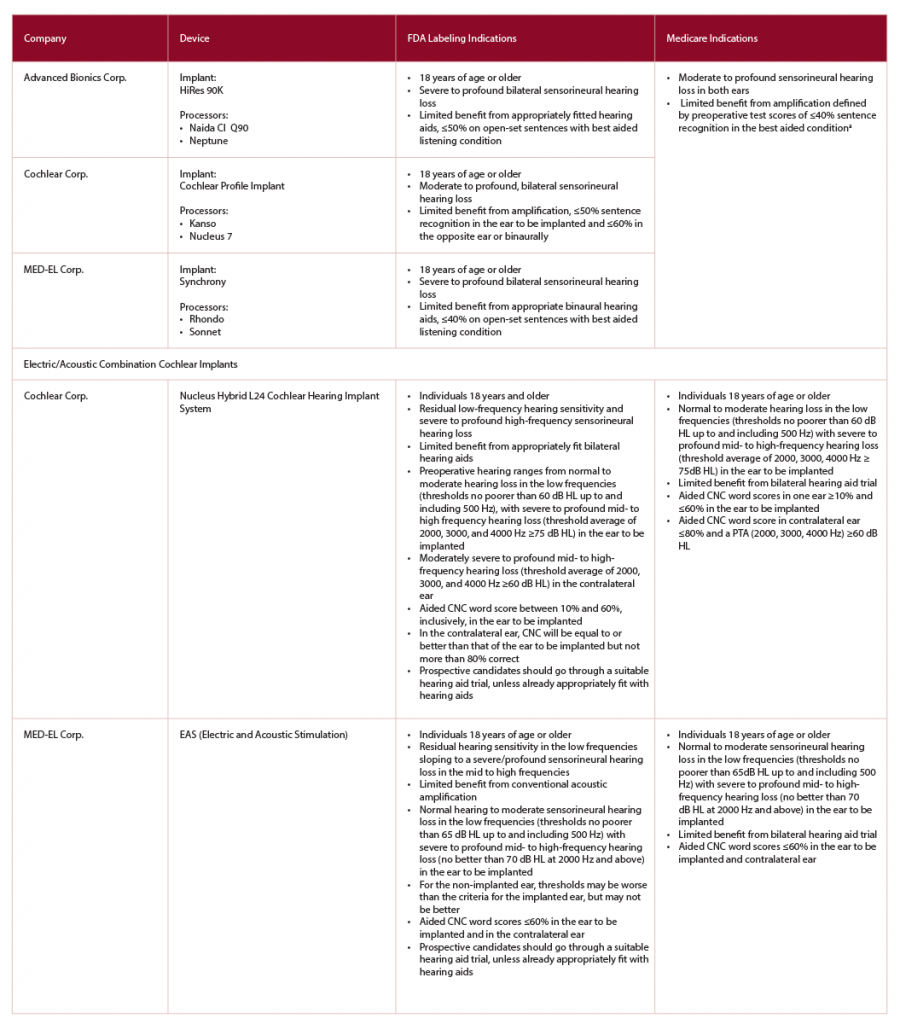

Identification of candidates for cochlear implantation is a process that is still under debate. One problem is that there is not one set of criteria for candidacy. In fact, the criteria for implantation vary based on the individual manufacturers’ specifications (MED- EL, Cochlear Device, and Advanced Bionics), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines, and individual insurance carriers.

“I don’t think anyone who does cochlear implants believes that the guidelines are adequate,” said Debara L. Tucci, MD, professor of head and neck surgery and communication sciences at Duke University Medical Center and medical co-director of Duke’s cochlear implant program. “Those of us who work with these patients see a large number who fall in the middle—they are no longer benefiting from a well-fitted hearing aid, but they don’t quite meet the criteria for a cochlear implant,” she said.

In an attempt to improve the criteria for cochlear implants, a group of experts met in 2011 and modified the battery of tests used to determine implant candidacy to better reflect real-world experiences (J Acoust Soc Am. 1994;95:1085–1099; Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:624–628). The AzBio Sentence Test, which replaced the HINT test, uses both male and female voices speaking in normal cadence and is conducted with and without background noise. “These tests help clinicians quantify the candidates’ functional hearing before implantation, and are also important for measuring post-implant outcomes,” Dr. Blackburn explained.

“There are ongoing studies through the American Cochlear Implant Alliance, where we are working together with CMS to expand their criteria for people with more residual hearing,” said Craig A. Buchman, MD, Lindburg Professor and chair in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Most guidelines recommend cochlear implants starting at one year for children with severe bilateral hearing loss, but some centers perform implants earlier (at nine months of age). There is no upper age limit for implantation, according to experts. As long as a patient fits candidacy criteria and is deemed medically fit for general anesthesia and surgery, he or she is considered a candidate. The procedure usually takes between one and two hours, with the patient typically sent home that day. Dr. Tucci recently implanted a 94-year-old man “who is sharp as a tack and doing beautifully.”

A recent study by Mudery and colleagues found that older adults (those with an average age of 73 years) had a 71% improvement in AzBio scores in quiet and a 51% point improvement in noise on the implanted ear. When hearing was measured on both sides, the researchers found bilateral hearing improved 23% points in quiet and 27% points in noise (Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:187-191). They concluded, “All patients undergoing CI candidacy testing should be tested in both quiet and noise conditions. For those who qualify only in noise, our results demonstrate that cochlear implantation typically improves hearing both in quiet and noise.”

Bilateral versus Unilateral CIs

Part of the confusion over the guidelines is whether to place one or two cochlear implants in patients with bilateral hearing loss. Some of these decisions come down to cost.

“The medical profession is very aware of the need for bilateral hearing. We have been saying this for years with regards to hearing aids—you need two ears. But for some reason, it has taken us longer to begin that conversation with cochlear implants,” Dr. Blackburn noted. “There is an auditory perceptual advantage to hearing bilaterally. The brain is more efficient at filtering out background noise when auditory information is received from both sides.”

The benefits of bilateral hearing include improved speech understanding, especially in background noise; improved localization; and enhanced safety due to increased awareness of the auditory environment.

Although unilateral cochlear implants generally provide good speech understanding under quiet conditions, patients frequently report difficulty understanding speech and speech localization in noisy environments (Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;17:351-355).

In addition, “patients with bilateral implants report being less fatigued with the act of hearing at the end of the day,” Dr. Lalwani noted. “A person with a single CI is pretty tired at the end of the day—they have to expend a lot of energy to understand” their environment.

In general, simultaneous bilateral implants are more commonly performed in children than adults. “Children are lifelong learners, but their environment is very compromised in school with a lot of background noise,” Dr. Lalwani said.

Adults often present with different amounts of hearing loss in each ear. “Typically, we will choose to implant the poorer-hearing ear. If the patient gets good benefit, and particularly if the second ear does not benefit from amplification, we will often consider a second side implant,” Dr. Tucci said.

“If there is some residual hearing [substantial low-frequency residual hearing] in the contralateral ear, that ear is managed with a hearing aid,” Dr. Buchman added. “In most cases, the implant and hearing aid together are better than a cochlear implant alone. However, when people recognize that the hearing aid is not providing a lot of value and they are struggling substantially, that is when we consider a second cochlear implant.”

“Most insurers are agreeing to pay for bilateral cochlear implants, but the cost effectiveness of bilateral implantation is not easy to prove, not because patients do not benefit, but because we don’t have accurate ways of measuring either the deficits without a second side CI or the benefits of bilateral implantation,” Dr. Tucci said.

When CROS Is a Better Option

Bilateral cochlear implants are ideal for patients with bilateral deafness, but when having two cochlear implants is not an option, patients may benefit from Contralateral Routing of Signal (CROS) to a cochlear implant, Dr. Buchman noted. This device is indicated for patients with a single cochlear implant and profound hearing loss in the unimplanted ear. The CROS microphone is placed on the unimplanted ear, which delivers sound wirelessly to the cochlear implant, creating access to sounds otherwise not available.

The CROS device and bilateral cochlear implants have not been directly compared. But the CROS system’s microphone is not directly stimulating the ear, Dr. Tucci noted; instead, “it routes the sound to the other [implanted] ear. One would think that directly stimulating the ear would be a better situation. Probably less ideal, but still beneficial.”

Changes in Technology

(click for larger image) Table 1: Comparison of Cochlear Implant Candidacy between FDA-Approved Devices and Medicare Adult Criteria

CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services;

CNC, consonant-vowel nucleus-consonant;

FDA, Food and Drug Administration

a Medicare is considering expanding criteria to include those individuals with more residual hearing—≤40% sentence recognition in the ear to be implanted and ≤60% in the opposite ear.

The most dramatic change in technology has been the shrinking of implantable stimulators. Compared with the original implants, the new stimulators are approximately 50% of their thickness or less, Dr. Buchman noted. This has enabled surgeons to create reliable implant fixation while avoiding the need for a bony seat or recess for the device in most instances. Now, the devices can slide under the temporal periosteum or muscle alone. “They don’t stick up as much [from the skull] and there are fewer skin reactions related to the site,” Dr. Buchman said.

All three stimulators, Dr. Lalwani said, look very similar and contain sophisticated electronics that are designed not to fail. “The expectation is that the CI will last a lifetime,” he added. Dr. Buchman agreed: “The new implants have become much more reliable, both the internal and external devices, which is really good news.”

In addition to the thickness of the implant, there have been advances in the design of the electrodes that run from the stimulator into the cochlea. “There is evidence that the outcome after cochlear implant is not as good when there is trauma to the cochlea compared to atraumatic procedures [Ear Hear. 2013;34:413-425]. The electrodes that attach to the cochlea implant have also gotten much smaller, thereby reducing the risk of damaging the fragile structures inside the cochlea,” Dr. Lalwani said.

Today’s external processors are like mini-laptop computers. There are a number of pre-processing strategies taken from hearing aid technology that improve performance. One example is the use of dual or directional microphones, Dr. Buchman said, “which has been very helpful in improving hearing in noise.” Fortunately, many of the older speech processors for implants can have their operating systems upgraded by the manufacturers, Dr. Buchman added.

In addition, manufacturers are working on improving battery life. Pre-curved electrodes that hug the cochlear modiolus have the potential to extend battery life between charges. “If the electrode is placed closer to the nerve endings, the amount of energy required to stimulate the nerve is less. The theoretical advantage is that with less energy required for nerve stimulation, more precise stimulation with less interaction in channels that are adjacent to each other is possible,” Dr. Lalwani said.

Wearing options have also improved patient satisfaction. “Cochlear implants used to be a technological wonder, but it has now become a consumer product in the sense that you have all these choices to make with respect to color, size, shape—all sorts of things,” Dr. Lalwani said. One company makes a waterproof speech processor (Advanced Bionics) that allows users to swim underwater, which is especially important to children, Dr. Lalwani noted. Other companies also have products that protect the external component from water damage.

Most of the devices now have Bluetooth wireless connectivity that allows the implant to be connected to a cellphone or other devices. External microphones, or FM systems, that relay the information from the speaker directly to the implant are also available—“this improves the signal-to-noise ratio and substantially improves performance in noise,” Dr. Buchman said.

Hybrid and EAS Implants

One of the expanding goals of cochlear implants is to maintain or preserve hearing. Right now, many people who have age-related hearing loss—hearing loss in the high-frequency basal turn, but preserved low-frequency hearing in the apical end of the cochlea—are not candidates for cochlear implants. For these patients, the implantation of a hybrid device may be a great option.

There are currently two such devices: Cochlear Hybrid Hearing by Cochlear Corporation and EAS (Electric and Acoustic Stimulation) by MED-EL. Both devices use shorter electrodes and are therefore less likely to traumatize the apical end of the cochlea, Dr. Lalwani explained. The devices are only placed where there is hearing loss isolated at the basal turn of the cochlea. “The goal is to have the electrode be short enough not to traumatize the inner ear, preserve the low-frequency hearing, and only stimulate the hearing in the high-frequency nerve fibers,” he added.

“By preserving the low-frequency hearing, patients are able to utilize their residual acoustic hearing in the implanted ear. This approach opens the doors for a broader range of hearing losses to benefit from this technology [combined electrical and acoustical hearing],” Dr. Blackburn added.

“Emerging indications are finding great utility in select populations,” Dr. Buchman said, “including patients with single-sided deafness and/or those with hearing loss together with incapacitating tinnitus. Amazingly, the cochlear implant can drastically reduce tinnitus in some patients. For people with single-sided hearing loss, they have significant improvement in sound localization and hearing in noisy environments. And for the EAS or hybrid implants, those patients can show significant improvement in performance that more closely approaches normal hearing than anything that we have had before.”

Social Cost of Hearing Loss

Ten percent of the U.S. population has significant hearing loss, Dr. Buchman noted. A number of studies have looked at the psychosocial impact of hearing loss. Perhaps most upsetting to patients and family members is the social withdrawal. “The number one comment I hear from patients is that they feel alone and isolated because of the hearing loss—it impacts their ability to communicate and affects their relationships with family and friends,” Dr. Blackburn said.

Older patients are especially vulnerable. A family member often brings in these patients. “I frequently hear, ‘At the Thanksgiving dinner table, my mother or father used to be extremely engaged and now they are not participating in the conversation because they can’t hear it—and they are becoming more and more socially isolated,’” Dr. Tucci said.

Social isolation has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of depression, while hearing loss is also associated with a variety of negative health outcomes (Lancet. 2017 Jul 10. pii: S0140-6736(17)31073–31075). These can include:

- Higher incidence of falls;

- Greater association with dementia and cognitive decline;

- Increased rates of hospitalization; and

- Higher overall cost of care.

“All of these things are at tremendous cost to society. It is to our advantage [as a society] to figure out how to accurately identify and treat hearing loss of all types, not just for patients who are candidates for a cochlear implant,” Dr. Tucci said. Dr. Buchman agreed: “Cochlear implants are transformative for those people in need.”

Nikki Kean is a freelance medical writer based in New Jersey.

Financial disclosures: Craig A. Buchman, MD, is on the Medical Advisory Board of Advanced Bionics Corp. and Cochlear Corp. He also has ownership equity in Advanced Cochlear Diagnostics, LLC. Anil K. Lalwani, MD, is on the Medical Advisory Board of Advanced Bionics and the Surgical Advisory Board of MED-EL. Debara L. Tucci, MD, has disclosed that MED-EL has funded the Newborn Hearing Screening Program pilot in Nairobi, Kenya.

Hospitalists as Test Subjects

- Heubi C, Choo D. Updated optimal management of single-sided deafness. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:1731–1732.

- Trinidade A, Page JC, Kennett SW, Cox MD, Dornhoffer JL. Simultaneous versus sequential bilateral cochlear implants in adults: Cost analysis in a U.S. setting. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:2615–2618.

- O’Connell BP, Hunter JB, Wanna GB. The importance of electrode location in cochlear implantation. Laryngoscope Inv Otol. 2016;1:169–174.

- Moberly AC, Houston DM, Castellanos I. Non-auditory neurocognitive skills contribute to speech recognition in adults with cochlear implants. Laryngoscope Inv Otol. 2016;1:154–162.

- Francis HW, Jennifer A. Yeagle JA, Thompson CB. Clinical and psychosocial risk factors of hearing outcome in older adults with cochlear implants. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:695–702.