Clinical guidelines are an increasingly important way for physicians and other health care providers to apply the best evidence to clinical practice. Many of these guidelines come from medical specialty societies such as the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgeons (AAO-HNS) and are driven, in part, by the need for specialties to identify their own best practices amid wide variation in clinical practice and the increasing complexity of health care delivery. The primary aim of guidelines is to give clinicians a tool that, along with clinical judgment and experience, helps them provide the best patient care possible.

Although clinical guidelines are becoming a larger part of medical parlance and practice, ambiguities remain about what they are and are not, how they are developed and how they should be used. The various terms used to denote these guidelines also muddy the waters. Here is a primer on the nuances of clinical guidelines.

Background

The emergence of clinical guidelines can be traced to the evidence-based medicine movement that took hold in the 1990s. A landmark article by Guyatt and colleagues published in 1992 described evidence-based medicine as an emerging paradigm for medical practice in which clinical decision-making is based more on

evidence from clinical research and less on intuition and unsystematic clinical experience (JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420-2425). The study emphasized the need for physicians to learn new skills to apply the evidence-based method to clinical practice, including how to conduct efficient literature searches and to apply the formal rules of evidence evaluation of the clinical literature. An editorial published in 1996 further laid the foundation by stating that “evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” (BMJ. 1996;312:71-72). This movement sparked a greater focus on advancing medical care by attempting a more systematic, scientific approach to clinical care.

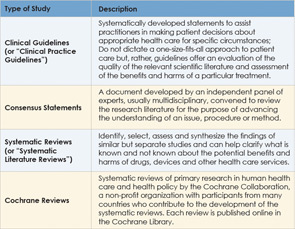

Along with clinical guidelines, other types of evidence also emerged to help guide clinical practice, such as consensus statements, systematic reviews of the literature, Cochrane reviews, protocols and practice parameters. Although all of these types of evidence-based methods are aimed at helping clinicians base clinical decisions on current evidence, clinical guidelines are distinguishable because they combine a rigorous systematic approach of identifying and evaluating the best evidence on a given clinical question with offering recommendations or statements of action to guide clinical decision-making (see Table 1, at left).

The terms “protocol” and “practice parameter” are often used interchangeably with “clinical guideline,” although these types of evidence do not always match the methodologic rigor required of guidelines as specified by criteria established in the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation instrument widely used to measure guideline quality (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(6 Suppl 1):S1–43). An understanding of how clinical guidelines are developed may help clarify how these guidelines differ from other types of evidence.

Developing Clinical Guidelines

A number of criteria have been proposed to develop clinical guidelines. A study published in 2008 identified key aspects commonly used among the various approaches (Implement Sci. 2008;3:45). These include: identifying clinical questions or problems; systematically reviewing and appraising the literature; drafting recommendations; external consultation and review; and a planned update. This process should be done by a multidisciplinary panel with input from consumers. In addition, a number of criteria designed to assess the quality of clinical guidelines have been proposed. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation and the Conference on Guideline Standardization are two commonly used criteria.

Another set of criteria commonly used by guideline developers has been established by one of the main organizations disseminating clinical guidelines. The National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), a publicly available database of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines formed in late 1998 under the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, currently disseminates about 2,700 guidelines. All guidelines published through the NGC must meet its criteria.

Even with the plethora of criteria available, many guidelines do not meet quality standards. A 2011 report by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) attributed this problem to shortcomings in the development of guidelines and proposed its own criteria to ensure trustworthiness. The IOM recommends that high-quality clinical guidelines:

- Be based on systematic review of the existing evidence;

- Be developed by a knowledgeable, multidisciplinary panel of experts and representatives from key affected groups;

- Consider important patient subgroups and preferences;

- Be based on explicit and transparent processes that minimize distortions, biases and conflicts of interest;

- Provide a clear explanation of the logical relationships between alternative care options and health outcomes and rate both the quality of evidence and the strength of the recommendations; and

- Be revised as appropriate when new evidence warrants modifications of recommendations.

The IOM also proposed standards for developing trustworthy guidelines. It urges attention to:

- Transparency;

- Managing conflict of interest;

- Composition of the group developing the guidelines;

- Intersection of clinical practice guidelines and systematic review;

- Establishing evidence foundations for and rating strength of recommendations;

- Articulation of recommendations;

- External review; and Updating.

The IOM is urging the AHRQ to pilot-test these standards to assess their reliability and validity.

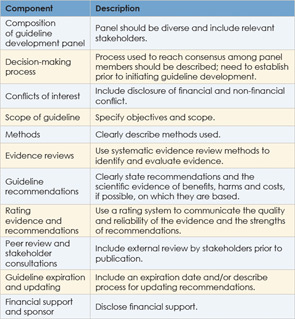

Further effort at ensuring the quality of clinical guidelines comes from the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N), a network of guideline developers from 46 countries that currently contains more than 3,600 clinical guidelines. In 2012, G-I-N proposed key components for guideline development aimed at establishing an international standard for guideline development (Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):525-531) (See Table 2, at left).

Misperceptions of Clinical Guidelines

The main aim of clinical guidelines is to improve the quality of patient care by providing physicians and other health care professionals with the best evidence on which to base clinical decision making. The goal is not to replace the judgment and experience of clinicians but to augment those critical tools with the most up-to-date, vetted and evaluated evidence. They should not be considered cookbook medicine. “Guidelines simply represent the best judgment of a team of experienced clinicians and methodologies addressing the scientific evidence on a particular topic,” said Rosenfeld and Shiffman.

Status of Guidelines: AAO-HNS

Currently, the AAO-HNS has published eight clinical guidelines. Given the intensive labor and high cost involved, the academy has published only one or two guidelines per year since 2006. According to Robert Stachler, MD, chair of the panel that developed the most recent AAO-HNS guideline on sudden hearing loss, these guidelines are models that other medical societies refer to when developing their own guidelines.

Leave a Reply