The Stark law and the Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS) are the U.S. healthcare system’s primary fraud and abuse laws, and highly anticipated proposed reform plans from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the Office of Inspector General (OIG) were finally unveiled on Oct. 17, 2019.

Explore This Issue

February 2020The proposed reforms would 1) clarify certain requirements and concepts under existing regulations and 2) allow certain compensation arrangements between parties that participate in alternative payment models and other novel financial arrangements touted by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Despite efforts by the CMS and the OIG to closely coordinate the proposed changes, healthcare providers may still be left interpreting and navigating two sets of slightly different rules and standards.

The Stark Law

© elwynn; Roman Zaiets / shutterstock.com

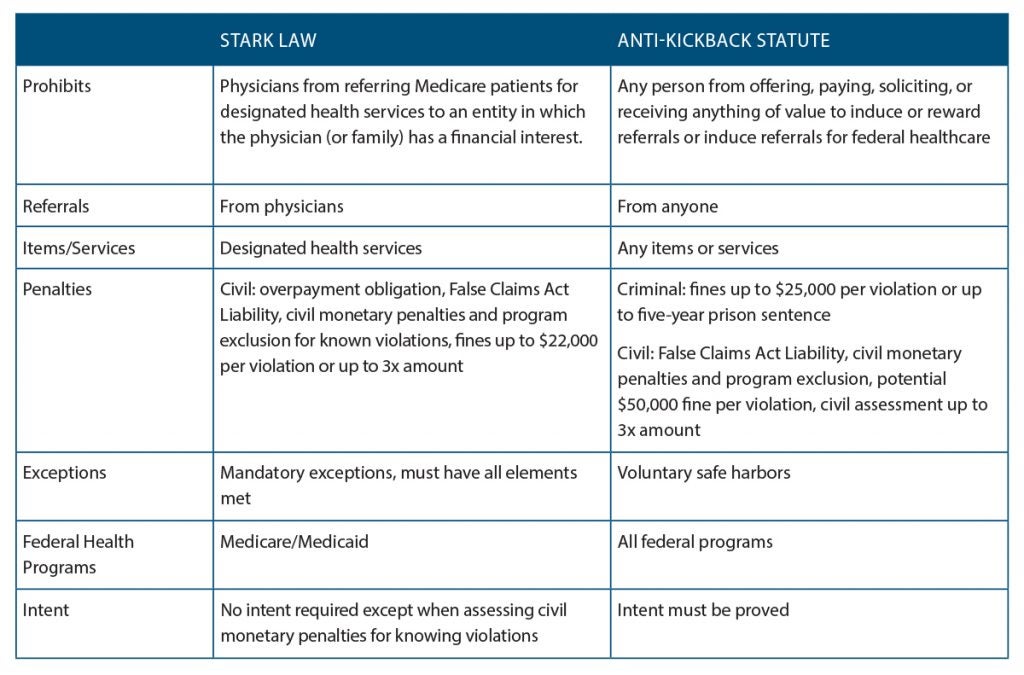

Also known as the Physician Self-Referral Law, the Stark law prohibits physicians from making referrals for designated health services payable by Medicare to an entity with which they or an immediate family member have a financial relationship—unless an exception applies. In addition, the Stark law prohibits the entity receiving the referral from filing claims with Medicare or billing another individual, entity, or third-party payer for those referred services.

Common statutory exceptions under the Stark law include those for space or equipment leases, in-office ancillary services, fair market value, physician recruitment, and personal service arrangements.

To qualify for a Stark law exception, all requirements of the exception under the Code of Federal Regulations (42 CFR § 411.357) must be met or the provider could be subject to civil monetary penalties, regardless of intent.

The Anti-Kickback Statute

The AKS prohibits physicians from offering, paying, soliciting, or receiving a direct or indirect payment in return for referrals for items or services paid for, even in part, under a federal healthcare program. Common safe harbors under the Anti-Kickback Statute include those for space or equipment rentals, investment interests, personal service and management contracts, practice sales, and referral arrangements for specialty services.

To qualify for an AKS safe harbor, all elements of each safe harbor under the Code of Federal Regulations (42 CFR § 1001.952) should be met; however, a provider’s intent is also relevant. Failure to fit squarely into a safe harbor does not necessarily mean that an arrangement violates the AKS, but the arrangement is subject to heightened scrutiny.

The CMS & the OIG are proposing four new value-based exceptions, or safe harbors.

New Exceptions Proposed

The CMS and the OIG hope to boost value-based initiatives and referral price transparency. The proposed changes give physicians more flexibility to improve quality of care while encouraging collaboration between providers, and collaboration between providers and patients. Transparency and seamlessness within the healthcare system are core concepts of the proposed reforms, although, for now, the CMS stopped short of requiring providers to inform patients of the cost of seeking additional services at the referral stage.

The CMS and the OIG are proposing four new value-based exceptions or safe harbors:

- Shared Data Services: To improve patient care coordination, a specialty physician practice could share data analytics services with a primary care physician practice.

- Coordinated Patient Discharge: Hospitals and physicians could work together in new ways to coordinate care for patients being discharged from a hospital. The hospital could provide the discharged patients’ physicians with care coordinators to ensure that patients receive appropriate follow-up care and share data analytics to help physicians ensure that their patients are achieving better health outcomes. Remote monitoring technology could also be used to alert physicians or caregivers when a patient needs a healthcare intervention to prevent unnecessary emergency department visits and readmissions to hospitals from which they were discharged.

- Smart Pillboxes: A physician practice could provide smart pillboxes to patients without charge to help them remember to take their medications on time. The practice could also provide a home health aide to teach the patient and caregiver(s) how to use the pillbox. The pillbox could automatically alert the physician practice and caregiver when a patient misses a dose so they could follow up promptly.

- Shared Cybersecurity Software: Hospitals and physicians often share information about their patients, so it’s important to ensure that no weak links compromise patient health or information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Under the proposed rules, a local hospital could improve its cybersecurity and the cybersecurity of providers it works with regularly by donating (i.e., free of charge) cybersecurity software to each physician who has access to the hospital’s network in connection with services referred to the hospital. Such software would improve the security measures in place for all users accessing a hospital’s network, minimize the risk of a hacker attack, and prevent hackers from spreading an attack to other physicians and hospitals whose systems are interconnected.

Terms and Concepts

The CMS and the OIG are proposing clarifications to the definitions of fair market value, volume or value, and commercially reasonable in the exceptions provided by the Stark law and the AKS.

Fair Market Value

Many of the Stark exceptions or AKS safe harbors require compensation for any services provided under the contemplated arrangement (e.g., sales and marketing, professional healthcare, billing) to be at fair market value, a concept that varies greatly by the service, geographic location, provider, and other factors. The CMS would define fair market value as “the value in an arms-length transaction, with like parties and under like circumstances, of like assets or services, consistent with the general market value of the subject transaction.” This CMS definition would incorporate the concept of general market value—the price the assets or services would bring as the result of bona fide bargaining between a buyer and seller in the subject transaction on the date of acquisition of the assets or at the time the parties enter into the service arrangement.

In its proposed rule, the OIG acknowledged the difficulty of reconciling the notion of fair market value with value-based arrangements and requested further comments specifically on that concept as a requirement.

Volume or Value

The CMS and the OIG noted that looming penalties may have a chilling effect on models and arrangements designed to reduce overall costs and improve quality of care. That’s because many cost-saving practices relate to patient referrals and shared or free services, which violate the traditional volume or value of referrals prohibitions under both the Stark law and the AKS. The CMS has proposed various revisions to the definition and the development of an objective standard or bright line tests in the proposed rule, which it hopes to finalize after reviewing public comments.

Commercial Reasonableness

The CMS and the OIG are considering how to define an arrangement as commercially reasonable, but disagree about the final language. Both debate whether to even require that value-based arrangements be commercially reasonable.

The CMS put forth two possible definitions for commercial reasonableness:

1) “The particular arrangement furthers a legitimate purpose of the parties and is on similar terms and conditions as like arrangement;” or 2) “The arrangement makes commercial sense if entered into by a reasonable entity of similar type and size and a reasonable physician of similar scope and specialty.”

Despite efforts to closely coordinate the proposed changes to the Stark law and the Anti-Kickback Statute, healthcare providers may still be left interpreting and navigating two sets of slightly different rules and standards.

It also stated that “an arrangement may be commercially reasonable even if it does not result in profit for one or more of the parties,” indicating that no party has to actually profit from an arrangement to infer commercial reasonableness.

The OIG’s proposed definition places emphasis on the reasonableness of an arrangement itself, setting aside any referrals generated, and states that a “commercially reasonable arrangement is an arrangement that would make commercial sense if entered into by reasonable entities of a similar type and size, even without the potential for referrals.”

Public Comment Period Closed

The proposed changes to the Stark law and AKS were open for public comment through Dec. 31, 2019. Although the proposed rules aim to clarify these confusing laws, considerable ambiguity remains. Healthcare providers should continue to exercise caution in forming value-based arrangements and business relationships that don’t fit neatly into a Stark exception or one of the AKS safe harbors.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney with McDonald Hopkins LLC. Contact him at sharris@mcdonaldhopkins.com.

Steven M. Harris, Esq., is a nationally recognized healthcare attorney with McDonald Hopkins LLC. Contact him at sharris@mcdonaldhopkins.com.

Reprinted with permission from the American College of Rheumatology.