Explore This Issue

March 2014

Management

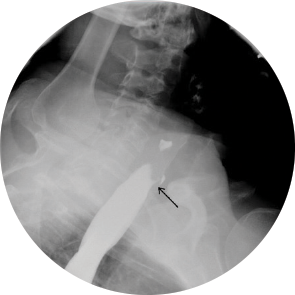

The upright study showed no abnormalities, but the recumbent examination revealed a 1 to 2 mm diameter tracheoesophageal (TE) fistula from the anterior margin of the cervical esophagus at the level of C6. Bronchoscopy was performed and revealed a pinpoint opening in the posterior membranous portion of the proximal trachea, about 13 cm from the incisors, which would open and close with inspiratory and expiratory movement. Esophagoscopy showed a fold in the esophageal mucosa corresponding to the area of opening in the trachea (Figure 2). The fistula was repaired through a transcervical approach.

Discussion

Congenital tracheoesophageal fistulae are caused by a failure of the tracheoesophageal septum to separate the presumptive larynx and trachea from the foregut around day 50 of embryonic life. H-type fistulae, like the one presented here, result when the tracheoesophageal septal defect is small.1 Although TE fistulae are often associated with other congenital malformations, their absence can allow H-type fistulae to persist undetected past the postnatal period. The incidence of TE fistulae in newborn infants is 0.03%, and H-type fistulae make up only 2% of these rare cases.2,3 Within this small subset of patients born with H-type fistulae, most are diagnosed shortly after birth. In fact, there have only been 17 cases in the English literature of adults presenting with H-type TE fistulae.4

Because TE fistulae are so uncommon, they are not often included on the differential diagnosis and can therefore be difficult to diagnose. A presentation of a persisting, nonproductive cough with a long history of coughing, pulmonary infections, and the presence of congenital anomalies should raise clinical suspicion of H-type TE fistulae. As demonstrated in this case, angulation of the fistula can keep the patient asymptomatic for a long time. With the tracheal opening lying above the esophageal opening, the fistula is angulated, allowing air to pass from the trachea into the stomach more easily than objects from the esophagus into the airway.5

Intraoperatively, it may be difficult to identify the fistula tract if it is small in caliber. Visualization with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), while injecting air or methylene blue, can help locate the fistula tract. In our case, because the TE fistula could not be located upon the surgical field, the tracheal opening was visualized with EGD, and a guidewire was placed through the trachea. During the neck exposure, it is important to directly visualize and identify the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) to prevent RLN injury. Another possible complication of the operation is recurrence of the TE fistula.6 In this case, we mobilized a muscle flap of the sternothyroid muscle and secured it to the wall of tissue between the trachea and esophagus in order to promote healing and reduce the chance of recurrence.

References

- Geller K, Kim Y, Koempel J, Anderson KD. Surgical management of type III and IV laryngotracheoesophageal clefts: the three-layered approach. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:652-657.

- Depaepe A, Dolk H, Lechat MF. The epidemiology of tracheo-oesophageal fistula and oesophageal atresia in Europe. EUROCAT Working Group. Arch Dis Child. 1993;68:743-748.

- Black RJ. Congenital tracheo-oesophageal fistula in the adult. Thorax. 1982;37:61-63.

- Hajjar WM, Iftikhar A, Al Nassar SA, Rahal SM. Congenital tracheoesophageal fistula: a rare and late presentation in adult patient. Ann Thorac Med. 2012;7:48-50.

- Lam CR. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of “H-Type” tracheoesophageal fistulas. World J Surg. 1979;3:651-657.

- Lal DR, Oldham KT. Recurrent tracheoesophageal tistula. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2013;23:214-218.

Leave a Reply