TRIO Best Practice articles are brief, structured reviews designed to provide the busy clinician with a handy outline and reference for day-to-day clinical decision making. The ENTtoday summaries below include the Background and Best Practice sections of the original article. To view the complete Laryngoscope articles free of charge, visit Laryngoscope.com.

TRIO Best Practice articles are brief, structured reviews designed to provide the busy clinician with a handy outline and reference for day-to-day clinical decision making. The ENTtoday summaries below include the Background and Best Practice sections of the original article. To view the complete Laryngoscope articles free of charge, visit Laryngoscope.com.

Background

A large vestibular aqueduct (LVA) is the most common inner ear anomaly found on the imaging evaluation of children with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). It is frequently associated with syndromic and nonsyndromic forms of SNHL or as an isolated finding. Large vestibular aqueduct syndrome can be characterized by delayed-onset, fluctuating, asymmetric, unilateral or bilateral SNHL or mixed hearing loss. Knowledge of an LVA is useful for practitioners to counsel their patients on avoiding contact sports or other activities with risk of head trauma. Others use the diagnosis to prompt testing for mutations in the EYA and PDS genes, looking for associated conditions such as Pendred syndrome. Currently there is debate between the best initial imaging modality to use when evaluating patients who have passed the newborn hearing screen but are presenting with idiopathic delayed-onset SNHL and are suspected of having an LVA.

Best Practice

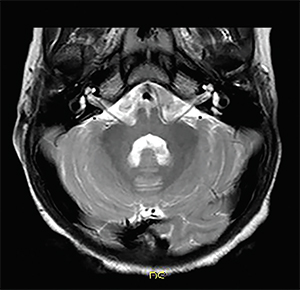

Asymmetric enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct (on right).

© Living Art Enterprises / Science Source

If the clinician takes the narrow viewpoint of which imaging modality should be used to diagnose an LVA, CT should be the initial study of choice based on the best current available evidence. In reality, however, for the patient who presents with idiopathic delayed-onset SNHL suspected of having LVAS, choosing between CT and MRI is made on a patient-by-patient basis. Risks and benefits of each modality should be tailored to the patient by considering the patient’s age, comorbidities, cost, and clinical setting. In addition, whether the hearing loss is unilateral or bilateral is important. Computed tomography scan is somewhat better at demonstrating cochlear and vestibular dyscrasias, whereas the MRI scan is better to show soft tissue lesions of the internal auditory canal and brain. For example, in a child with bilateral, profound SNHL, an MRI scan may be preferred in a cochlear implant evaluation to exclude conditions such as cochlear nerve aplasia.

The dramatic advancements in MRI technology necessitate a more current study to accurately compare sensitivity of present-day MRI versus CT in diagnosing LVA. In addition to continued refinement of existing MRI hardware and pulse sequences, higher field strength MRI scanners (i.e., 7 Tesla) have the potential to further improve the resolution of inner ear structures, particularly as challenges with susceptibility artifact are overcome. Therefore, this question will need to be re-addressed in an ongoing fashion as imaging technology, both MRI and CT, continually improves (Laryngoscope. 2016;126:302-303).