© Mark Winfrey / shutterstock.com

Among the many changes healthcare has undergone within the last four decades, one of the most notable is where outpatient surgeries take place. In 1981, 19% of all surgeries in the United States were outpatient procedures performed either at a hospital outpatient department or an ambulatory surgical center (ASC). By 2011, this number was at 60%.

Data show that over half of all outpatient surgeries done in the U.S. in 2017 were performed in an ASC, up from 32% in 2005. This growth continues, with outpatient procedure volumes forecast to increase by 14% to 16% from 2016 to 2026 (Health Affairs. 2014;33:764–769).

If current trends hold, an ever-growing number of these outpatient surgeries will be done in an ASC. In terms of revenue, the ASC market is projected to increase to $40 billion in 2020, up from $32 billion in 2018.

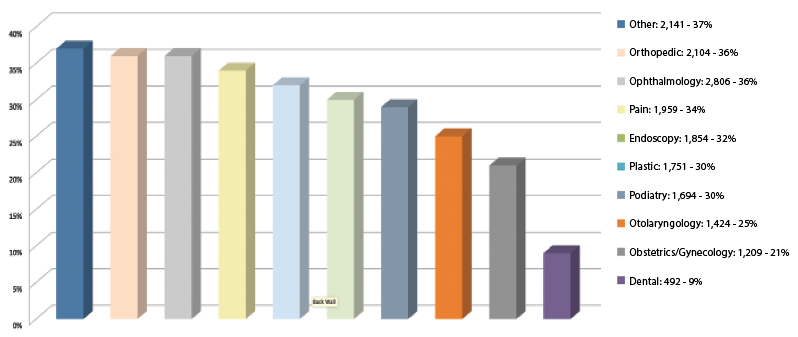

Within this dynamic surgical landscape is a shift in the types of procedures being done in outpatient surgical settings and in ASCs in particular. Advances in anesthesia, surgical technique, and instrumentation (i.e., minimally invasive surgery), as well as a widening inclusion of procedures covered by Medicare, has driven a number of specialties to expand into ASCs. As of June 2019, the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association (ASCA), citing data from CMS, report that ophthalmology and orthopedics are the specialties that perform the most surgical procedures in Medicare-certified ASCs (36% each). Specialties performing in the middle include pain procedures (34%), endoscopy (32%), plastic surgery (30%), podiatry (29%), obstetrics/gynecology (21%), otolaryngology-head and neck surgery (21%), and dental (9%) (see Figure 1).

Otolaryngology certainly makes the list, but why the seemingly slower uptake by otolaryngology to transition more procedures to an ASC?

The big difference is that you have more control over cost. Ambulatory surgical centers are well able to manage and reduce expenses and make it a less costly endeavor to render care for payers and providers. —Ralph P. Tufano, MD, MBA

Ralph P. Tufano, MD, MBA, the Charles W. Cummings MD professor of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, noted that many otolaryngology procedures, such as sinus surgery, facial cosmetic surgery, and tonsillectomy, are good candidates for outpatient surgery. But complex procedures, such as those related to head and neck cancer, require inpatient surgery. He also cited restrictions on hospital-based otolaryngologists who may not be able to perform procedures in an ASC because of contractual agreements or lack of an ASC affiliated with the hospital that employs them. “Our field is trying to wrestle with this,” he said.

Dr. Tufano said he thinks private practice otolaryngologists are doing a good job of using ASCs to do many of their bread-and-butter procedures such as tubes, tonsils, and sinus surgery. He also sees a trend in academic otolaryngologists using multispecialty versus single-specialty ASCs. CMS data cited by the ASCA supports this: Only 1% of otolaryngology ASCs were single-specialty, versus 48% that were multispecialty.

Figure 1. Otolaryngologists have taken advantage of Medicare-certified ASCs for some of the more standard otolaryngologic procedures.

Source: ASCA (https://www.ascassociation.org/advancingsurgicalcare/asc/whatisanasc).

ASC Benefits for Otolaryngology

ASCs offer a number of benefits for otolaryngologists. Among those most often cited are cost reductions and improvements in efficiency when performing appropriate procedures in an ASC, because in ASCs, physicians can more easily handle scheduling, assemble their own surgical teams, and manage their own equipment needs than they can in a traditional hospital outpatient setting. “The big difference is that you have more control over cost,” said Dr. Tufano. “Ambulatory surgical centers are well able to manage and reduce expenses, making it a less costly endeavor to render care for payers and providers.”

Data bear this out. A Health Affairs cost analysis of ASCs looked at whether or not the centers are less costly than hospital outpatient departments by focusing on efficiency and surgical times. The analysis found that procedures performed in ASCs took on average of 31.8 fewer minutes than those performed in hospitals, representing a 25% difference relative to the mean procedure time (Health Affairs. 2013;33:764–769). Shorter procedure times mean more scheduling time freed for additional procedures, increasing revenues.

James Stankiewicz, MD, professor and chair in the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Loyola University Medical Center in Maywood, Ill., who has been doing outpatient procedures in an ASC for many years, underscored the efficiency of ASCs compared to hospital outpatient or inpatient surgical centers. Unlike in hospital surgical settings, he noted that surgeons and others who perform procedures in the ASC setting have more control over all aspects of healthcare delivery, including billing, staffing, and scheduling. “In an ASC, things are more coordinated and organized [compared to hospital surgical settings, where surgeons have less personal control], and things get done in a better fashion,” he said.

Unlike more complex and broad surgical cases that are done in outpatient hospital settings, the less complex cases done in the ASC, he said, “tend to be shorter cases with less difficulty, [where] the outcomes are sometimes more predictable,” which greatly affects cost.

A report by the ASCA also highlights the annual savings from procedures performed in ASCs versus hospital outpatient departments, estimating a savings of $37.8 billion per year. This number reflects 48% of common ASC procedures covered by private payers. The report further estimates that an additional $41 billion in healthcare costs could be saved yearly if the percentage of procedures done in an ASC increased.

An additional benefit, beyond improving efficiency and reducing cost, is the potential for increased revenue that results from performing more procedures that can be done in an outpatient hospital setting. Otolaryngologists who invest in an ASC and become physician-owners also are able to generate additional revenue by receiving a share of the ASC facility payments. To date, a majority (69%) of ASCs are partially or fully physician owned.

To reap these benefits, however, otolaryngologists need to ensure that patients selected for outpatient procedures are appropriate, and they need to prioritize patient safety measures.

Complexity of the case and the complexity of the patient determines if a procedure should be done at an ambulatory surgical center. —James Stankiewicz, MD

Focus on Patient Selection and Safety

Careful and appropriate patient selection is key to ensuring that an ASC is the appropriate venue for a surgical procedure. Several factors go into selecting the appropriate patient, including the patient’s overall health, the type of procedure, and the skill of the surgeon.

“Complexity of the case and the complexity of the patient determines if a procedure should be done at an ASC,” said Dr. Stankiewicz, adding that a lot of otolaryngology procedures can be done in an ASC.

Along with the most common procedures, he said he also knows of surgeons who perform tympanomastoidectomies and cochlear implants in an ASC. Dr. Stankiewicz, as a rhinologist, performs primary or revision polyp surgeries in the ASC, along with certain cerebrospinal fluid leaks and skull-based cases limited to the nose, without any gross involvement in the brain area.

Of importance, however, is that the ASC Dr. Stankiewicz works at is near a university and is, therefore, in close proximity to hospital care if needed. “By working next to a university hospital, I can get instrumentation, such as those that allow for image-guided surgery,” he said. “Some ASCs may not have that access, so that will limit the types of procedures otolaryngologists can do.”

Having easy access to higher-level care is key to ensuring patient safety, particularly for more complex cases and patients, such as those on dialysis, who are contraindicated for ASC use. Even less complex procedures may occasionally encounter unexpected complications, such as inadvertently hitting a major vessel, resulting in a bleed, or a reaction to anesthesia

or medication.

For all ASCs, regardless of proximity to a hospital, having an escape plan to transfer a patient from an ASC to a hospital if needed is crucial. “It’s important that every ASC have a transfer agreement, meaning a hospital that you will work with to transfer a patient to if there is a problem,” said Jedidiah Grisel, MD, an otolaryngologist with Texoma ENT & Allergy in Wichita Falls, Texas.

Mimi S. Kokoska, MD, MHCM, CEO and co-founder of Accend Health, a value-based healthcare management consulting company in California, said it is important to create a plan to manage an untoward event that may arise. “How would one handle significant and unexpected bleeding intraoperatively or postoperatively?” she said, citing other problems for which a plan is needed, such as airway compression after thyroidectomy.

Dr. Kokoska, who has experience working in surgical leadership roles in both academic and community health systems, underscored the added stress to the patient of transferring to a hospital and the associated costs to the patient and the ASC, as well as liability issues for the ASC and surgical team related to patient morbidity and mortality. That said, however, she reiterated the need for proper selection of patients to minimize the chances of an unplanned event. This selection, she said, starts with taking a holistic view of the patient.

For example, when considering the appropriateness of thyroid surgery in an ASC, the first step is to consider the whole patient—what is their medical history? What are their risk factors for complications? If the patient is generally healthy, the next step is to consider the appropriate surgical setting and team in terms of anesthesia, necessary equipment, frozen pathology as needed, and support if something goes wrong.

A good candidate for thyroid surgery in an ASC, Dr. Kokoska said, would be a healthy patient undergoing a partial or hemithyroidectomy for whom the risk of complications is very low in an experienced physician’s hands. Patients for whom a total thyroidectomy is needed are more controversial, however, given the higher risk of airway compression from postoperative bleeding and higher risk of hypocalcemia, vocal cord paralysis, and airway compression, she said.

A further consideration is surgical skill. “Total thyroidectomy can be done in an ASC, but it depends on the surgeon’s skill in preserving the recurrent laryngeal nerves [and] parathyroid glands, and minimizing bleeding,” said Dr. Kokoska. “For a surgeon who’s starting out, I would recommend holding off on performing a total thyroidectomy in an ASC until the surgeon has had much more experience.”

Find a company with a track record of doing high-quality work with patient safety as a priority, and follow their rules, and allow a professional group to help you ethically run the ASC. —Jedidiah Grisel, MD

Although Dr. Tufano said that there is no strong evidence to suggest that airway compression risk from hematoma is higher in patients who undergo total thyroidectomy, he agrees that careful patient selection is needed. “We have to be very thoughtful about who can undergo a thyroidectomy in an ASC, and establish strict selection criteria,” he said, agreeing that a partial thyroidectomy is typically a low-risk intervention in a healthy patient. For instance, “I wouldn’t choose a 65-year woman who has a massive substernal goiter going down into her chest [and] who also has COPD for a thyroid lobectomy or total thyroidectomy in an ASC,” he said.

For any procedure undertaken at an ASC, it comes down to good planning and teamwork. “It takes a team who does this type of surgery all the time, with consistently excellent outcomes, to put together a thoughtful protocol of how to select appropriate patients and then implement the care in an ASC,” said Dr. Tufano.

As part of that planning, ASCs may want to ensure that there is a clinician on board who’s certified in advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) and/or pediatric advanced life support (PALS). A recent survey by the Leapfrog Group, a Washington, D.C., watchdog group focused on healthcare quality, found that while all ASCs in the survey had ACLS-certified personnel on site, only 89% had someone PALS certified on site, much lower than the 96% of hospital outpatient facilities. (Otolaryngology was among the 10 specialty groups surveyed.)

Otolaryngologist Opportunities: Setting Up an ASC

As with other specialties, otolaryngologists can choose different ways to set up or work in an ASC. In the Leapfrog Group survey, most ASCs participating reported that the type of ASC they belonged to was a joint venture between physicians and a management company (38%). Single physician or multiple physician-owned ASCs accounted for 29%, while 18% were jointly owned by physicians and hospitals, and 8% were owned by physicians, a management company, and hospitals.

Eugene Brown, MD, RPh, a practicing otolaryngologist in an ASC and president of Charleston ENT & Allergy–The Surgery Center of Charleston, S.C., offered several broad recommendations for otolaryngologists interested in setting up an ASC. These include knowing the laws governing how to set up or invest in an ASC, as these laws vary by state; getting advice from experts on opportunities to set up an ASC in a particular region; the benefits and potential downsides of different business arrangements (e.g., some of the perks of corporate management options from joint venture partners could get lost); and seeking ownership in an ASC, as this offers greater autonomy and oversight in surgical care, as well as additional revenue.

Dr. Grisel, who is in the process of developing a new ASC in a city of 100,000 people two hours north of Dallas, described his ASC as multispecialty (orthopedics, otolaryngology, and neurosurgery) and a joint venture with a management company.

His ASC will provide “commoditized” procedures, he said, meaning somewhat elective procedures like tubes and tonsils that currently are being performed at a high cost inefficiently in a level III trauma center.

The ASC will also offer “stay suites” or overnight lodging attached to the ASC for patients who may need 24-hour observation following surgery. Home health workers will attend to patients. “This allows you to safely increase the volume of cases you bring at the ASC,” said Dr. Grisel, adding that the idea for these overnight suites came from orthopedists who use them for patients undergoing joint replacement surgery who need observation after surgery.

As an investor in the ASC, Dr. Grisel spoke to the concerns that investor physicians may have a conflict of interest in treating patients in a facility in which they have a financial stake. “The best way of doing this is to partner with a group who knows how to do it well,” he said. “Find a company with a track record of doing high-quality work with patient safety as a priority, and follow their rules, and allow a professional group to help you ethically run the ASC.”

Another innovation in ASC development is to consider bundled payments, in which providers and/or facilities receive a single payment for all the services performed to treat a specific care episode, in addition to fee for service. “If you’re smart about it, with proper risk assessment it can be a good way to keep reimbursements from encountering a race to the bottom” in pricing, he said.

“This incentivizes everyone to have really high-quality surgery,” he added, saying that bundled payments have been used by orthopedic surgeons for some time. “I can see the day when things like tonsils and thyroids could be engaged in that sort of relationship with payers where we get a bundled lump sum, but then we own that patient for 30 days,” he said.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.

AAO-HNS Position Statement on ASCs

Debashish Debnath, MD, an oncoplastic breast surgery fellow at Wythenshawe Hospital in Manchester, U.K., provides a useful list of best practices when treating physician colleagues in his published

article, “The Dilemma of Treating a Doctor-Patient: A Wrestle of Heart Over Mind?” (Ochsner J. 2015;15:130-132):

- Take a history and perform a thorough examination (as you would for any other patient).

- Deal with the physician-patient’s anxiety directly.

- Clarify the doctor/patient relationship as early as possible.

- Avoid overly close identification with a physician-patient because of empathy or sympathy.

- Discuss the treatment management plan in detail.

- Leave plenty of time for a clear discussion of opinions and recommendations.

- Speak to the physician-patient directly. If relatives need to be spoken to separately, it should be done with the physician-patient’s consent.

- Discuss issues of privacy, confidentiality, insurance, and payment early.

- Maintain professional courtesy at all times.