The most dreaded complication of parotidectomy is facial nerve injury which is fortunately rare. A less devastating consequence that occurs in some patients is a pre-auricular depression caused by the absence of the parotid gland. While the problem is cosmetic, patients may feel uncomfortable with their appearance.

Explore This Issue

August 2016

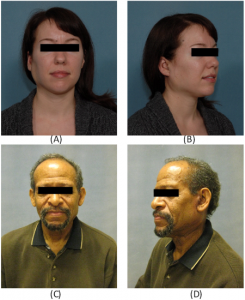

Two-week postoperative visit showing overcorrection of a right (A, B) and left (C, D) parotidectomy defect with free abdominal fat transfer reconstruction.

A number of surgical techniques to reconstruct this parotidectomy defect are available, including bipedicled sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle flaps, AlloDerm biomaterial, free tissue transfer, and free abdominal fat transfer (FAT). A recent study published in The Laryngoscope examines the use and effectiveness of the FAT transfer in reconstruction, including a realistic look at complication rates. The investigators say the procedure is technically simple and, when performed at the time of parotidectomy, improves facial symmetry and achieves excellent postoperative cosmetic results. (Laryngoscope [published online ahead of print May 30, 2016]. doi: 10.1002/lary.26025).

FAT Graft Procedure

In the study, 105 patients underwent 108 parotidectomies with FAT reconstruction between 2007 and 2015. The majority of patients had benign pathology and tumors that were smaller than 3 cm. Superficial parotidectomy was performed in 62 patients, and concurrent elective neck dissection was performed in eight patients.

During the FAT procedure, according to corresponding author Christine Gourin, MD, professor of otolaryngology in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, a large piece of fat, along with some connective tissue, is removed from the abdominal area. “Rather than using a large incision, I prefer a pariumbilical incision,” said Dr. Gourin. “Not only are patients generally happier with the

Postoperative results six months after free abdominal fat transfer following right (A, B) and left (C, D) parotidectomy.

Credit: © 2016 The American Laryngological, Rhinological and Otological Society, Inc.

appearance, as the incision is cosmetically hidden, but a large incision in the area can mimic an appendectomy scar. That could be catastrophic if emergency medicine surgeons saw the scar and made an assumption that the patient had had other abdominal surgery, leading to a misdiagnosis of abdominal pain.”

One primary complaint about using standard fat grafts for parotidectomy defect reconstruction has been fat reabsorption and liquefaction. Although this may be a concern for fat harvested through liposuction methods, as well as for AlloDerm, which does not work well for filling substantial gaps, Dr. Gourin said that the connective tissue acts as an anchor to keep the transplanted fat in place. “Generally, the surgeon would take 30% more abdominal fat than what’s needed to repair the defect because despite the connecting tissue acting as an anchor, some reabsorption will happen, but with a large piece there is a better chance of the tissue surviving in its new location,” she added.

Only perhaps half of parotid surgeons perform [the FAT procedure], and I think its use depends to some extent on the age of the surgeon and where he or she trained. It wasn’t something I learned to do in my training; many of us just weren’t exposed to techniques for parotid defect reconstruction. —Christine Gourin, MD

Advantages, Disadvantages, and Complications

Although FAT grafts are a viable option for parotidectomy defect reconstruction, Dr. Gourin was surprised at the abdominal complication rate, with hematoma in eight patients and seroma in three patients. “The abdominal complication rate of 10% was a little higher than I thought it would be, but it really is the result of taking a large fat graft through a small incision,” she said. “But it’s a pretty realistic rate of donor site complications, and it’s important to report those honest data.”

Other complications reported included the following:

- Parotidectomy wound dehiscence occurred in six cases (6%); all of these patients responded to conservative management.

- Fat transfer graft debulking was required in three patients with persistent overcorrection beyond six months postoperatively. According to Dr. Gourin, one patient lost a great deal of weight, and two patients did not have the absorption rate originally predicted. No patients demonstrated undercorrection or further FAT resorption beyond six months.

- There were no significant differences between the FAT and control groups with respect to postoperative drain output, duration of drainage, and facial nerve function.

- Although Frey’s syndrome can also occur, no patients in this study reported the condition or required Botox injections for it.

Contraindications

Gustatory sweating during starch-iodine test following parotidectomy.

U.S. National Library of Medicine

Dr. Gourin noted that, based on her experience since her last study on the FAT graft technique in 2008, she has found some contraindications for its use (Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1186-1190). “If you’re excising skin along with the parotid gland, then the closure is under increased tension and the FAT graft will further increase that tension. In that case, I wouldn’t consider doing one.”

Although the FAT procedure is a technically simple reconstructive option when performing parotidectomy, it isn’t as commonly used as SMC flaps. “Only perhaps half of parotid surgeons perform it, and I think its use depends to some extent on the age of the surgeon and where he or she trained,” said Dr. Gourin. “It wasn’t something I learned to do in my training; many of us just weren’t exposed to techniques for parotid defect reconstruction.

“It also depends on whether you view a parotid defect as a cosmetic problem and how much you discuss it pre-surgery with patients,” she added. “Many patients don’t ask about reconstruction because they don’t expect a defect. I offer it during consultation because after a parotidectomy and the shock of the tumor wears off, other concerns like appearance often come to the front. It isn’t vanity—it’s returning to the state they were in before the operation. I’d love to see this technique in greater use. If I ever had a parotid tumor, I would want this done.”

Amy E. Hamaker is a freelance medical writer based in California.

Key Points

- There are a number of surgical techniques for reconstructing this parotidectomy defect, including bipedicled sternocleidomastoid muscle flaps, AlloDerm biomaterial, free tissue transfer, and free abdominal fat transfer.

- Autologous fat grafts have long been used in the reconstruction of facial defects, and the advantages of utilizing fat include its abundant availability, biocompatibility, and ease of harvest.

- The main criticism of fat grafting has been reabsorption and longevity of the material.

Preventing Frey’s Syndrome

Frey’s syndrome, or gustatory sweating, is a known complication of parotid gland surgery. Placing a barrier between the overlying skin flap and the parotid bed during repair can often prevent the syndrome. A recent study published in The Laryngoscope examined how effective FAT grafts are for preventing Frey’s syndrome (Laryngoscope. 2016;126:815-819).

Shaoxin Wang, MD, an otolaryngologist with the department of head and neck surgery at the Sichuan Cancer Hospital and Institute in Sichuan, China, and his colleagues performed a prospective randomized trial on 36 patients who underwent parotidectomy and were randomly assigned to abdominal free fat or acellular dermis grafting groups (18 patients in each group). The researchers then evaluated the occurrence of Frey’s syndrome, aesthetic outcome, economic results, and other complications.

Not only did the authors find that both techniques prevented Frey’s syndrome equally well, but patients who had free fat graft transfers were more satisfied with their appearance and paid less for the operation than their counterparts.

Study Details

- A total of 36 patients (27 male and nine female) with a median age of 57 years were enrolled. Eighteen patients each were allocated to the acellular dermis group and the free fat graft group. One of the 18 patients in the acellular dermis group experienced gustatory sweating over the preauricular regions six months after the operation. (This patient also had a positive starch-iodine test.)

- No patient in the free fat graft group complained of Frey’s syndrome symptoms.

- The incidence of objectively diagnosed Frey’s syndrome was 11.1% (2/18) in the acellular dermis group and 5.6% (1/18) in the free fat graft group after starch iodine testing. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (Fisher’s exact test).—AH