Ed. Note: This piece was written by Dr. Wei in early April, while the U.S. was still reeling from the mass shooting of eight people in Atlanta spas and massage businesses, six of whom were Asian women.

Explore This Issue

May 2021Words can’t describe my emotions as I pulled up to the curb at Orlando International Airport yesterday and saw my father and stepmother (ages 77 and 73) sitting on a bench waiting for me. My parents arrived here to stay for the month of April. It’s been 17 months since I last saw them, and so much has happened in the last few weeks..

I greeted my father enthusiastically as I helped him put his carry-on luggage in the trunk of my car. My frail, too-thin stepmother stood with a cane and waited patiently at the curb. It’s always been awkward to hug Asian parents, both my own and those of my friends. Growing up, we just don’t hug. I hugged her anyway.

As I held her severely osteoporotic, thin frame, a massive lump (globus sensation) filled my throat, and I held back my tears. I was afraid I’d break her if I squeezed. But thanks to my emotional state, brought on by the events of the past few weeks, in my mind my stepmother was also the 65-year-old Filipino woman who was kicked in the head repeatedly in New York City while a security guard watched and turned his back on her. She was also the 70-year-old Chinese woman attacked in San Francisco who courageously fought back. I hugged them all.

Words also can’t describe my intense feelings over the past 14 days. After juggling busy clinics and ORs, solving countless system challenges, facing decreased resources against returning clinic volume and low division morale after two rounds of reduction in force and more resignations, and dealing with my own physical and emotional pain, I come home to my family and try to catch up on current events. The news recap shows horrific violence and a seemingly endless list of mass shootings and incredibly misplaced anger at Asians and Asian Americans over COVID-19.

The March mass shooting at Atlanta area day spas was an awful example of a long history of dehumanizing Asian women, but it was just another of the more than 2,800 hate incidents that have occurred across the U.S. since March 2020.

The March mass shooting at Atlanta area day spas was an awful example of a long history of dehumanizing Asian women, but it was just another of the more than 2,800 hate incidents that have occurred across the U.S. since March 2020. Most people are unaware of the other cases simply because they received little or no media attention.

For the next 30 days, here at home, my parents will be safe. I will make sure they won’t experience anti-Asian violence. I’ll take them out to eat at a few restaurants that have their favorite cuisine, and I’ll cook everything they love. We will shop, and I’ll spoil them however I can, despite their frugal nature. They will protest the expense. We will sit and enjoy tea in the beautiful scenery of my backyard and take slow walks.

Understanding My History

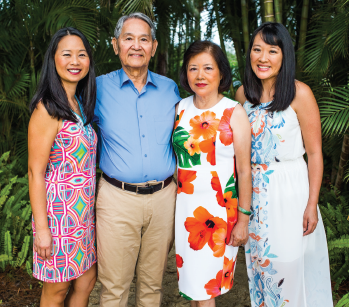

The author, Julie L. Wei, MD (left), with her parents and sister.

© Courtesy Julie L. Wei, MD

I didn’t realize the intensity and depth of the emotions I had been suppressing for the past several decades as an Asian American. I may be perceived as a typical “successful” Asian American surgeon and academician, a daughter who fulfilled the Asian American “dream.” But others, including my own Caucasian husband, don’t know what I’ve endured over my entire adult life in this country. I have rarely talked about it; I’ve perhaps even normalized my experience in order to better focus on what I need to accomplish. Few colleagues have asked how I was doing, or about my parents and families, despite ongoing coverage of anti-Asian violence.

Who are Asian Americans? Who are our beloved parents and relatives who are victims of violence and hate crimes, mass shootings, racist remarks, spitting, and other behaviors of anti-Chinese, anti-Asian xenophobia? The answer isn’t easy, because we’re a lot of different people with some stories in common. I can tell you my story because it may be similar to those of my fellow Asian American colleagues in our specialty and others.

In June 1980, I boarded my first flight on China Airlines from Taipei to Los Angeles at age 10, sitting next to a woman whom I now call “mom” just eight months after my mother died from her three-year battle with breast cancer. I knew we were going to America and was quite uncertain about it, as I had no idea that I wouldn’t be able to communicate with that new world, leaving the only country and environment I had ever known. I was leaving my four aunties who had helped to raise me during my mother’s near-continuous hospitalization in the late 1970s. I was leaving all of my cousins, and my father, who was to join us three months later.

Key memories of America during those times include moving out of my uncle’s house and into our first apartment, with nothing more than a six-pack of 7-Up and a loaf of white bread. There were frequent shopping trips at the Salvation Army, living humbly while helping my father with his first coffee shop venture in Burbank, making rubber thong slippers in our apartment living room to sell for 25 cents each, and helping to care for and raise my half-sister while I was still a child myself. My parents still look for bargains and save everything. I once told a dishwasher salesman to stop trying to upsell a more expensive model to my parents—they were really looking for something that would serve as the ultimate drying dish rack, and they would continue to wash dishes by hand.

Living My Experiences

These are some of the defining moments that make up who I am now. But it’s humbling to realize that now, at age 51, I know little about the American history of cyclic and systemic racism against Asians from various countries and cultures. While I was fulfilling the “model minority” stereotype of a hardworking and academically accomplished Asian student, neither the U.S. history AP classes I took nor the textbooks I read included the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the decades of political complexities of foreign policies and attitudes against specific countries, or the anti-human rights issues.

Those who know me professionally may not know what I and our other Asian American colleagues have endured for years, and even today, in terms of anti-Asian and gender-based bias, racism, and xenophobia. For years, despite always introducing myself as “Dr. Wei” during patient encounters, I found myself suppressing disbelief and anger when, at the end of the visit, after thoroughly explaining the indications, risks, and goals of a surgical procedure, I was asked, “When will we meet the surgeon?” I was once even asked, “Where’s your accent?”

This is the country where my family and I have lived, succeeded, and made sacrifices, and where we’re raising children to become incredible American citizens who will contribute to society and their future communities.

I spent years telling myself it wasn’t because of how I looked, my Asian heritage, or that I’m a woman. I told myself people said these things out of innocent ignorance and unconscious bias. I was fine. Except that I wasn’t. I knew that my male and non-Asian colleagues probably weren’t being asked these questions on a weekly basis.

It has been about two years since I decided to “fix” this problem and save myself the feelings of embarrassment and inadequacy. For every clinic encounter, I walk in, pull my mask down and smile, and state clearly, “Hi, I’m Dr. Julie Wei. I’m a mother and I’m a surgeon.” I have to be clear so that there’s no room for intentional or unconscious bias.

One of our community’s excellent pediatricians is also a female Asian American, and in just the past two weeks while she was at a gas station, someone yelled racial slurs at her, spit at her, and told her to “go home.”

But this is our home. This is the country where my family and I have lived, succeeded, and made sacrifices; where I married a Caucasian and treated his grandmother with the same deep, traditional respect that I would treat my Asian grandmother with; and where we’re raising children to become incredible American citizens who will contribute to society and their future communities.

My heart has been full this month as every night I have enjoyed dinner with my parents, together within my arm’s reach. I had missed the inexplicable joy my father showed in gifting us, in his less-than-perfect grammar, with a plastic thermometer he had found at the dollar store (for 99 cents!). He reminded me that we can find joy in the smallest of things and acts, regardless of anger, sadness, grief, exhaustion, or whatever challenges we endure.

Dr. Wei is division chief of pediatric otolaryngology/audiology at Nemours Children’s Hospital and director of the Resident and Faculty Wellbeing Program at Nemours Children’s. She is also an associate editor on the ENTtoday editorial advisory board.

Fighting Hate

My cousins and I are working hard to raise awareness of anti-Asian sentiment by working through our own organizations, social circles, and communities. Each of us can take many actions to empower ourselves and help others. Here are a few things we’re doing.

- I’m grateful that at my own Nemours Children’s Hospital, our DRIVE (Diversity, anti-Racism, Inclusion, Value, and Equity) task force and steering committee have set up listening sessions and are planning town halls to increase awareness and connectedness for those who are impacted by current events and may be experiencing racism. Our CEO recently shared an enterprise message to voice support for all Asian American/Pacific Islander (AA/PI) associates. My sister has facilitated healing circles for the AA/PI community at her company by partnering with a Black employee network at her workplace.

- If you enjoy podcasts, check out this particular episode of Café Insider with former U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara.

- My younger sister inspired my cousins and me to sign up for the Hollaback free bystander intervention training to stop anti-Asian/American and xenophobic harassment. I resolve to never be a bystander who does nothing when witnessing harassment.

- To heal our patients, we must heal ourselves first. Medications and surgical procedures have never been enough. I’m committed to asking every patient family how racism and current events have affected them and to listening generously as a part of the holistic healing that must accompany my training and expertise. Together, we can suffocate the hate, racism, and xenophobia, and help humanity be at its best for our children and grandchildren.