Ongoing and emerging research is providing a fuller picture of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) as a spectrum of diseases that goes beyond the current clinical phenotyping, based largely on the presence or absence of nasal polyps, to a deeper recognition of distinct subtypes of the disease based on pathogenic mechanisms.

Explore This Issue

July 2019It is hoped that research into these subtypes will lead to the ability to use them as biomarkers to better predict how best to treat patients with CRS, particularly given the rapid development and availability of biologic agents aimed at targeting specific pathologic mechanisms of disease.

The need for improved tailored treatments for people with CRS is highlighted by the sheer number of people with sinusitis symptoms, a limited ability to adequately treat these patients based on symptoms, and the current reliance on the presence or absence of polyps. “The epidemiology of CRS is still a work in progress, but studies suggest that a huge number of people, probably 39 million in this country, have the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis,” said Robert Kern, MD, chair of the department of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, “Of those, I would estimate that perhaps 26 million or so really have sinusitis, confirmed by computed tomography, of which only approximately six million have polyps.”

Although targeting patients with polyps for treatment with intranasal and oral corticosteroids is the standard treatment approach, its impact on outcomes is less than satisfactory, he said. “Phenotyping or clinical evaluation alone has made only a limited impact on clinical care, or even the ability to tell a patient if they will do well or not on a given treatment,” he said.

To improve clinical outcomes, researchers like Dr. Kern are looking beyond clinical patterns of sinusitis into the patterns of tissue inflammation as a guide to better improve their ability to identify the patient subsets who will benefit from specific treatments. Called endotyping, the research looks at the underlying pathogenic mechanisms of disease, an approach that is similar to research that has already been conducted in the study of asthma and other atopic diseases.

For clinicians, this research, combined with ongoing studies into more advanced phenotyping based on attributes such as age and geography, highlights the need to look at CRS not as a singular disease, but as one with distinct clinical presentations and disparate—probably related—pathogenic mechanisms. “It is important to understand that all CRS patients are different,” said Justin H. Turner, MD, PhD, associate professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Vanderbilt University in Nashville. “CRS is a clinical syndrome, and patients may present very differently and have variable responses to medical and surgical interventions.”

In the future, we will be able to subdivide patient groups more precisely, and that will lead to rolling out precision, personalized medicine in which we can really predict from mucus or a blood sample how to treat patients. —Robert Kern, MD

Clinical Patterns and Subtypes

Although the presence or absence of nasal polyps is the cornerstone on which the current treatment of CRS is based, additional information on the clinical patterns of CRS is emerging that provides more direction for clinicians. These data point toward clinical indicators such as age, geography, ethnicity, and others associated with different underlying pathogenic mechanisms of CRS and, therefore, support the use of endotyping.

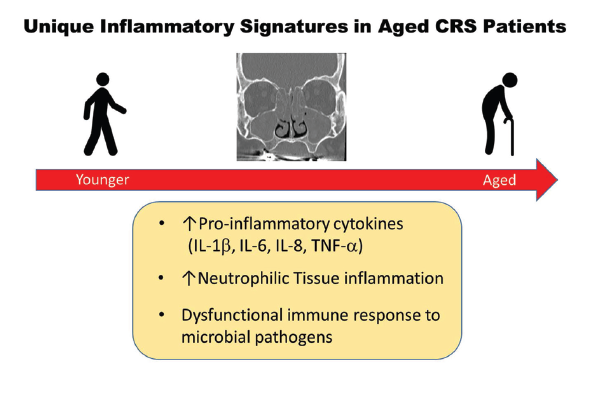

One area of research suggests the importance of age in distinguishing the type of inflammation and its potential impact on treatment outcomes. Dr. Turner and his colleagues recently published a study in which they found that older people with CRS had elevated tissue and mucus levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines associated with innate immune system dysfunction, were more likely to harbor colonizing bacteria in the sinonasal tract, and had more neutrophilic inflammation regardless of polyp status or other clinical variables when compared with younger patients (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:990–1002). “Older CRS patients may appear similar to younger patients on physical exam but differ in many other ways,” said Dr. Turner. “Given the unique inflammatory signature that we have identified in older patients, we feel that it is essential that age be taken into account when planning treatment approaches.”

Specifically, when examining tissue and mucus specimens of 147 patients ranging in age from 18 to 78 years who underwent sinus surgery for CRS, the investigators found that the inflammatory signature of a subgroup of patients older than age 60 was very different from that found in patients younger than 60. Whereas the inflammatory signature in the younger patients was characterized by a group of cytokines (Th2-associated) found in most CRS in North America, these cytokines were not significantly elevated in older patients. Rather, the inflammatory signature in the older patients was associated with a neutrophilic proinflammatory response characterized by an elevation in cytokines linked to the body’s innate immune function and acute and chronic inflammatory response. “You don’t see an elevation in those cytokines until around age 60, and then from that age on, there’s a progressive increase in the levels of those cytokines seen in the mucus and tissue of those patients,” said Dr. Turner.

One important implication of this finding is that current treatment approaches for CRS may be less effective in older patients. “Neutrophilic inflammation is typically less responsive to topical and systematic corticosteroids,” said Dr. Turner. “This would suggest that great care should be taken when prescribing repeated courses of oral steroids in older patients, and strongly suggests the need for alternative therapies to more effectively target this vulnerable population.”

Another area of research shows that people with CRS living in Asian countries are likely to have more neutrophilic inflammation than people living in Europe/North American countries. For example, a 2017 study found that most people with CRS in Europe/North America (80%) have nasal polyps characterized by increases in eosinophilic cytokines (type 2 inflammation), compared to 20% in China and 60% in Korea or Thailand (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1230–1239).

According to Amber Luong, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of otorhinolaryngology–head and neck surgery at McGovern Medical School of The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, the differences in the types of inflammation found in nasal polyps in these geographical populations highlights the fact that while people with CRS can look clinically similar (i.e., have the presence of nasal polyps), they are very different molecularly.

All CRS patients are different. CRS is a clinical syndrome and patients may present very differently and have variable responses to medical and surgical interventions. —Justin H. Turner, MD

She emphasized, however, that this is not an ethnic difference per se, adding that nasal polyps in second generation Asians with CRS living in Northern America or Europe are starting to look molecularly similar to nasal polyps in the populations of these countries. “This observation suggests that environmental exposure plays a critical role in driving the type of immune response contributing to rhinosinusitis,” she said. On the other hand, she cited a 2018 study that found that variations in cut-off levels of eosinophil numbers used to diagnose eosinophilic versus neutrophilic chronic rhinosinusitis may contribute to some of the differences in the percent of eosinophilic versus neutrophilic CRS between eastern and western countries (Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18:46). Nonetheless, she added, the 2017 study highlights the fact that not all polyps are the same at a molecular level.

To that end, she said the research is pointing toward the future. “Maybe down the road you can take a biopsy sample that helps us to endotype our patients with chronic sinusitis,” she said.

For Noam A. Cohen, MD, PhD, director of rhinology research in the department of otorhinolaryngology–head and neck surgery at Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, another important component of what he sees as a multifactorial approach to explaining CRS is looking at taste receptors and the role they play in the development of the disease.

In studies published in 2012 and 2014, he and his colleagues showed that people with sensitive bitter taste receptors are less likely to develop a subtype of CRS based on the genetically determined function of these taste receptors (J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4145–4159; J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1393–1405). The research showed that one bitter taste receptor detects the molecule secreted by gram-negative bacteria that subsequently stimulate an immediate defense (nitric oxide production) in the cells lining the sinuses, which kills and clears out bacteria that play a common role in sinusitis. “What the receptor triggers is like a switch turned on in response to the bacteria, which not only kills the bacteria but sweeps the dead bugs away,” said Dr. Cohen.

Where this gets interesting, he said, is that there are a lot of genetic differences in the ability of people to taste bitter molecules. “Over the past five to six years, we’ve been able to show that patients in whom this bitter taste receptor doesn’t work are at much higher risk for developing gram-negative sinusitis,” he said.

With this finding, Dr. Cohen and his colleagues then looked at whether you could use the presence or absence of functioning bitter taste receptors to predict surgical outcomes, and they found that a subset of CRS patients without the functioning receptor were at higher risk for sub-optimal surgical outcomes.

Currently, Dr. Cohen and his colleagues are gearing up to launch a clinical trial to see whether it is possible for patients with CRS to forego conventional antibiotics after activation of their multiple bitter taste receptors and natural defense mechanism against the bacteria that cause rhinosinusitis.

Patterns of Inflammation

The potential to identify specific molecular biomarkers of CRS to individualize treatment is being advanced through research on CRS endotyping, through which investigators are looking at the patterns of inflammation in the tissue of nasal polyps in people with CRS. “We still rely on phenotypes in the clinic,” said Dr. Kern, “but we can gaze at the future in terms of endotyping.”

A recent study by Dr. Kern and colleagues that looked at the presence of subsets of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) found that the subset ILC2 may play an important role in the development of type 2 inflammation found in patients with CRS and nasal polyps (Immun Inflammation Dis. 2017;5:233–243). In the study, the investigators used multiple techniques to look at the presence of subsets of ILCs in patients with CRS, both with and without nasal polyps. ILCs, along with T-helper lymphocytes, produce high levels of cytokines that are present in distinct patterns in the tissue. These patterns will likely define the clinically relevant endotypes, each of which will respond differently to current treatment options. Type 2 inflammation, defined by the presence of elevated type 2 cytokines (IL-4, 5 and 13), is present in the vast majority of patients with CRS with nasal polyps. This Type 2 endotype—or, more likely, a group of related type 2 endotypes—has been particularly difficult to treat, with a high recurrence rate after both medical and surgical therapy. Type 1 and Type 3 inflammations are less common and likely more responsive to treatment. In CRS patients without polyps, the inflammation is more heterogeneous, but a large percentage still exhibit Type 2 inflammation.

Figure 1. Unique Inflammatory Signatures in Aged CRS Patients.

Reprinted from J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:990–1002, Copyright 2019, with permission from Elsevier.

According to Dr. Kern, each pattern of inflammation will likely respond differently to various treatment options in ways that should be predictable. “We are still working this out,” he said, emphasizing that the research is only relevant if it has clinical application—that is, if it can shed light on the natural history of the disease, help predict who will respond to what treatment, and determine which patients will do well on a given treatment.

For Dr. Kern and others, this is the direction in which CRS treatments are heading. “In the future, we will be able to subdivide patient groups more precisely, and that will lead to rolling out precision, personalized medicine in which we can really predict from mucus or a blood sample how to treat patients,” he said.

Underscoring the need for further research is the emergence of biologic agents that can target specific mechanisms of disease, a treatment already used for patients with asthma. This advance is on the doorstep for patients with CRS. Dr. Kern pointed to results of a study recently presented at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology (AAAI) meeting in February 2019 that showed the safety and efficacy of the biologic agent dupilumab for nasal polyps (“Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps: results from the randomized phase 3 SINUS-24 study”).

According to Dr. Kern, the biologic agent will hopefully gain approval from the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of nasal polyps sometime later this year, representing a major advance in the ability to manage patients with severe CRS with nasal polyps.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.