Patients at the University of Michigan Health System who have experienced a bad outcome are likely to receive another visit from their physician. They are told the reason for the outcome and whether it was preventable or not, and the physician apologizes. If the physician or hospital was at fault, the patient is offered compensation.

This course of action is the basis of what is being called a “Michigan Model” for malpractice reform—an innovative approach to medical errors, mishaps, and near misses, implemented by the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor. Physicians and administrators at the University of Michigan say the program, which began in 2001, has achieved resounding success by a number of measures, including reduced malpractice claims and improved hospital-patient relations.

All that, and yet none of those measures is the primary overarching goal of the communication and resolution program at the university. It’s safety.

“The main goal is to get better,” said attorney Rick Boothman, chief risk officer at the University of Michigan Health System and architect of the Michigan Model. “We will never improve if we can’t admit our mistakes to ourselves. And we are brutally honest.”

Tangible Benefits

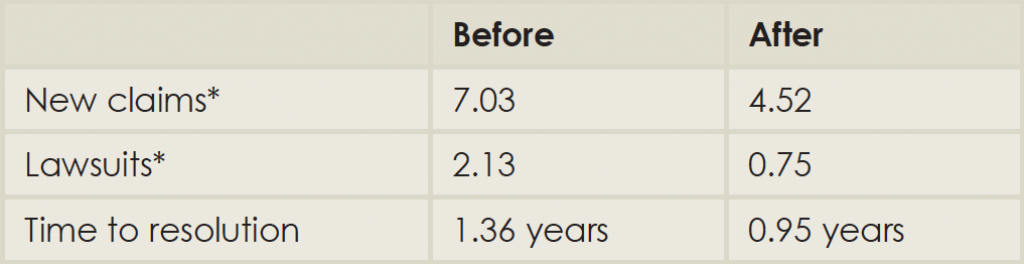

Boothman teamed up with some University of Michigan physicians to study the impact of the Michigan Model. They compared data from the six years before the program’s implementation with numbers from the six years after the model debuted. Post-implementation data revealed fewer claims and fewer compensated claims (See “Comparison of Claims before and after Implementation of the Michigan Model for Medical Errors,” below). Time to claim resolution was shorter, and claims-related costs were down as well (Ann Intern Med. 2010; 153:213-221).

“Doing the right thing paid off,” said Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, a co-author of the study. Dr. Saint is chief of medicine at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System, professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan and director of the university’s patient safety enhancement program. “If we’re at fault, we disclose and try to make the patient and the family whole. They can still hire an attorney if they want to, but otherwise things get resolved faster. Our openness helps us.”

More academic medical centers are following Michigan’s lead in providing full disclosure to patients. Stanford University’s program, called PEARL (Process for Early Assessment and Resolution of Loss), began on a limited basis in 2005 and launched as a full-fledged program in 2007. In its first three and a half years, the university reported a 36% decrease in claim frequency and a 32% average reduction in annual insurance premiums.

“Initially the concept was somewhat foreign,” said Edward Damrose, MD, an otolaryngologist at Stanford University Medical Center who will soon be chief of staff at Stanford Hospital. “Traditionally, doctors were taught: ‘Say nothing, admit nothing, and let the lawyers talk.’ Never say you’re sorry—that’s tantamount to admitting guilt.”

Stanford physicians quickly warmed to the idea, however. Dr. Damrose called it a breath of fresh air. “When something bad happens, doctors do feel sorry, even if they’re not at fault. It can be cathartic and liberating to say you’re sorry.”

At Stanford, the primary assessment determines whether a bad outcome was unanticipated and was preventable. Dying of a terminal illness, for instance, is anticipated, while a retained foreign body is a preventable, unanticipated event, and full disclosure is indicated. “We take ownership of the error: This is what happened, it was preventable, and we’re taking measures to keep it from happening to anyone else,” Dr. Damrose said.

The state of Massachusetts passed a “Disclosure, Apology, and Offer” law in 2012, a first in legislating such conduct of healthcare organizations. The law calls for a six-month “cooling off” period, during which the communication and resolution process should take place. After that, patients can still choose to sue healthcare providers if they want, although statements of apology will be inadmissible in court.

Dovetailing Trends

Many physicians and health policy researchers point to the influential 1999 Institute of Medicine report, “To Err is Human,” which documented the harms that physicians and hospitals sometimes inflict on their patients for a whole variety of reasons. The report called for greater transparency in healthcare.

Two years later, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations established new safety standards for patients, including disclosure of unanticipated outcomes.

These two influential organizations certainly helped turn the tide of practices that encouraged doctors and their patients to become adversaries in the courtroom. But a VA Hospital in Lexington, Ky., is widely credited with being the first healthcare facility to institute a full disclosure policy.

Two huge malpractice claims in a single year—1987—spurred the Lexington VA to take action. Intending to be more proactive in risk management practices, a committee bumped up against the ethics of informing patients when they may have been unaware of an error. In a 1999 paper describing the disclosure policy and its impact, then chief of staff Steve Kraman, MD, wrote:

The committee members decided that in such cases, the facility had a duty to remain in the role of caregiver and notify the patient of the committee’s findings. This practice continues to be followed because administration and staff believe that it is the right thing to do and because it has resulted in unanticipated financial benefits to the medical center” (Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:963-967).

Boothman was unaware of the Lexington story when the University of Michigan came to him for help in filling a staff job. He’d been a trial lawyer in private practice for 22 years, defending physicians and hospitals in malpractice suits. “Paradoxically, the better I got, the more likely I was to win a case I shouldn’t win, which ran counter to my clients’ long-term interests in quality and safety.”

He took the opportunity to share his thoughts about the medical malpractice system as a whole and about how the University of Michigan might change its process. “Michigan did not need a courtroom to know when the care was appropriate or not. I outlined for them, in essence, the Michigan Model,” he said. His first task was to circulate three interwoven principles: Patients harmed by unreasonable care should be made whole quickly and fairly; caregivers must be supported when care was reasonable; and the university must learn from its mistakes.

He found that the biggest resistance came from other lawyers. “This was not counterintuitive to physicians,” he said. “Almost across the board, the doctors and the healthcare leadership embraced this.” The university created a new position of chief risk officer, which reported to clinical leadership and not the general counsel.

Some lawyers benefit, he said. “By being honest, we help patients and we help their lawyers,” Boothman said. “Cases without merit are almost gone. The plaintiff’s bar understands the value of the approach.”

Do the Right Thing

“Patients trust us with their lives,” said Kevin Kavanagh, MD, MS, a retired otolaryngologist who now chairs the patient safety organization HealthWatch USA and is associate editor of the Journal of Patient Safety. He sees disclosure policies as a key tool in the prevention of adverse events. “It’s hard to have a culture of safety when you have a culture of denial and covering up errors. And disclosure is the ethical and moral thing to do.”

It’s the only way to have a quality assurance program that works, he added. “The errors I’ve been involved in, they’re often multiple levels of failure. A cascade of events, systems failures, more than one check that’s not working.” But by reporting and owning up to a mistake, physicians and their healthcare facilities can learn from it.

Dr. Kavanagh said disclosure policies should work equally well in smaller settings, such as a private practice. Although, given the fact that it is a culture change, it may take some practice—and support—to admit errors directly to patients. “I think we are hard-wired to perceive threats and to avoid them,” Boothman said, adding that the difficulty of admitting fault might be particularly acute in healthcare providers. “When things go badly, they take it personally and harder than most.”

Comparison of Malpractice Claims before and after Implementation of the Michigan Model

(Click for larger image)

*Numbers reported are per month per 100,000 patient encounters.

Source: Adapted from Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221.

The apology part of the process is difficult. It goes against one’s instincts, especially a physician who has practiced in a setting where mistakes are not generally permitted. Boothman once counseled an oncologist after a breast cancer diagnosis was delayed. They talked about the impact of the delay, and discussed sitting with the patient and the plaintiff’s lawyer. Boothman quoted the physician: “I would rather eat tacks.”

Dr. Damrose advises keeping the safety goals in mind. “When we’re talking to the patient and the family, we’re telling them what we learned from this and what changes we will put in place,” he said. Listening is equally crucial. The family sometimes simply needs to be heard, he added. “Sometimes they need to vent.”

Both Michigan and Stanford keep their physicians informed about the disclosure protocols: how to report an adverse event, whom to talk to, where to find support. Residents and faculty from other institutions undergo an orientation for the communication and resolution programs; current faculty get periodic refreshers at faculty meetings. Boothman reported that some incoming physicians have told him they came to Ann Arbor specifically because of the Michigan Model.

Both health systems also receive queries from other institutions. “I get maybe six calls a month,” Boothman said. He gets one of two responses from skeptics. Either he hears, “It could never happen here!” or “We’re already doing it.” “For years, physicians have been told to say nothing and let the risk management people deal with it,” Dr. Saint said. “We’ve been afraid to open ourselves up to lawsuits.”

The fear of being sued leads to some medical practices that have come under recent scrutiny, such as ordering up more tests and treatments so that the physician is protected from a frivolous lawsuit, said Dr. Saint.

The Michigan Model of communication and resolution is a huge departure from that tradition, but it also honors the medical creed: Do no harm. Rather than avoiding risk of lawsuits, it says physicians should avoid repeating mistakes. The reduction in malpractice claims and costs is simply a bonus. “The ultimate goal is to be open about the errors we make, to avoid making them again, and to avoid losing the trust of our patients and families,” said Dr. Saint.

“A lot of people say it’s the right thing to do,” Boothman said. “I never say that. I say: It’s the smart thing to do; it’s the necessary thing to do. Because if we’re going to look long term, the most important patient is the one we haven’t hurt yet.”

Jill Adams is a freelance medical writer based in New York.