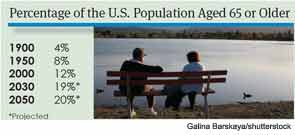

Odds are, you probably already see a fair number of older patients in your practice. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging, the number of older Americans has expanded dramatically in recent years. Between 1990 and 2009, the number of Americans older than 65 increased by almost nine million, reaching 39.6 million.

Otolaryngologists are already seeing the effects of this geriatric population boom. A 2012 study of a large, private ENT practice group in Georgia found that geriatric patient visits accounted for 14.3 percent of all patient encounters in 2004 and 17.9 percent of patient encounters in 2010 (Laryngoscope. 2012; Jul 2. doi: 10.1002/lary.23476). “The reality is that otolaryngologists already see a large portion of geriatric patients,” said Michael M. Johns III, MD, an associate professor of otolaryngology at Emory University in Atlanta and one of the authors of the study. He is also an ENT Today editorial board member.

The Administration on Aging predicts that there will be more than 72 million Americans over the age of 65 in the year 2030; Dr. Johns and his fellow researchers estimate that geriatric patients will account for a full 30 percent of all otolaryngology appointments at that time. Dr. Johns and other researchers wonder if otolaryngologists are truly equipped to handle this projected uptick. “The question is, is there enough capacity within our specialty to adequately care for these people, and are we really trained in geriatric medicine,” said Dr. Johns.

Adequate Treatment Begins with Appropriate Assessment

Dr. Johns and his colleagues found that five of the most common geriatric diagnoses, including hearing loss, vertiginous syndromes, otitis media and disorders of the inner and outer ear, are otologic. Head and neck cancer is also relatively common in the geriatric population. The average age of diagnosis for squamous cell carcinoma of the upper digestive tract is 59, and research shows that, with appropriate treatment, survival rates for geriatric patients can equal that of younger patients (Laryngoscope. 2003;113(2):368-372). Throat-related problems, including dysphonia and swallowing difficulties, are also common in the elderly (Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):332-335).

In the past, many clinicians—and their patients—dismissed certain ear, nose and throat problems as unavoidable parts of the aging process. “When patients come in and say, ‘Doctor, my voice is a little weak,’ there’s sometimes a tendency to say, ‘Well, what do you expect? You’re 80 years old,’” said Karen Kost, MD, president of the American Society of Geriatric Otolaryngology (ASGO). “But, surprisingly often, there will be some underlying pathology. Even if no pathology is found, there’s often something we can do. We can, for instance, augment the vocal cords with injections and rehabilitate their voice, making the patient much more functional. That’s why it’s really important to listen to patients and to search for treatable conditions.”

Otolaryngologists who specialize in the care of older patients say that appropriate care of the older population begins with an understanding of ENT-related diseases in the elderly, as well as a sense of compassion and understanding of the challenges older people face. “The assumption is that treating older people is the same as treating someone who is younger, with a few modifications,” Dr. Kost said. “But that’s like saying that a 5-year-old patient is just a miniature adult. Older patients behave differently in terms of disease processes and have to be treated as a distinct group.”

One of the challenges involved in caring for the elderly is that certain pathologies behave differently in older people. Head and neck cancer, for instance, may be more aggressive in older patients with multiple comorbidities, Dr. Kost said. Yet, older patients frequently face a treatment bias. “There’s a tendency to undertreat aggressive disease like cancer, and then have patients come back later because they were initially undertreated on the basis of their age,” Dr. Kost said. “To deny somebody appropriate therapy based on age alone is discriminatory. So it’s very important when assessing these patients not to look at chronological age, because in a lot of cases, it’s really not relevant. It’s really their functional status that’s important. If you have an 85-year-old who has minimal comorbidities, who lives with a spouse or on their own and is functioning independently, there is an excellent chance that the patient will tolerate aggressive treatment for an aggressive disease.”

Conducting a thorough assessment not only uncovers important comorbidities and functional limitations; it also allows physicians to find underlying pathology that may be missed if the practitioner focuses too much attention on the age of the patient. “Laryngeal cancer and vocal cord paralysis are more common as we get older, but we have to do our due diligence to assess for causes beyond age,” said Seth Cohen, MD, MPH, associate professor of surgery in the department of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Duke University in Durham, N.C. “There may be other serious factors that are going on.” The same holds true for other otolaryngologic diagnoses.

Understanding Quality of Life

Successfully treating the geriatric patient, however, requires more than diagnostic skill and expert medical intervention. Many geriatric patients suffer from multiple comorbidities, and it is essential to understand the complex interplay between patients’ physical condition and their functional status.

Hearing loss and dizziness, for instance, are extremely common in the geriatric population and can have a dramatic effect on patients’ quality of life. “Younger patients who have dizziness can often compensate pretty well, because their muscles, joints and vision are good,” said Neil Bhattacharyya, MD, associate chief of otolaryngology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. “But an 85-year-old with dizziness who also has arthritis of the knees, poor balance and cataracts has a triple hit against them.”

Similarly, hearing loss and age-related vocal changes can impact every part of a patient’s life. “Elderly people who have hearing loss and dysphonia are more likely to have higher depression scores and quality of life issues than people who don’t have hearing loss or vocal changes,” Dr. Cohen said. Otolaryngologists who work with older patients must consider patients’ living environments, communication burden, cognitive ability, values and comorbidities when designing treatment plans.

—Karen Kost, MD, American Society of Geriatric Otolaryngology

Of course, developing a thorough understanding of the patient’s quality of life takes time. Conducting a full history and physical of an older patient takes longer than it does for younger patients, in part because older patients typically have more extensive medical histories. “An 80-year-old almost always has a more complicated history than a 35-year-old,” said Jerry Goldstein, MD, a founding member of ASGO. Older patients may also have communication difficulties, including hearing loss, weak voices and possible memory loss, which make it difficult to quickly and easily obtain information.

Busy otolaryngologists may feel hard pressed to come up with the extra time to spend with elderly patients, but physicians who work with the geriatric population on a regular basis say the time spent is a worthy investment.

The Importance of Collaboration

For otolaryngologists who are used to treating pathology only, skillfully managing the care of geriatric patients may require a shift in focus. “We have to go beyond the diagnosis and look into patients’ quality of life,” Dr. Bhattacharyya said. “Are they safe at home? Or do they need some assistance? We have to advocate for our patients, too.”

Few, if any, otolaryngologists have time to act as patient case managers, so it’s essential for otolaryngologists to collaborate with other health care personnel. “We have to remember that we are not treating these patients in isolation,” Dr. Cohen said. “We may have to work with neurologists, pulmonologists and primary care physicians. Geriatric patients have lots of needs, and a lot of these problems are interrelated.” Tools such as electronic health records can help physicians communicate across disciplines; so can old-fashioned phone calls.

Busy practitioners can most effectively and efficiently care for geriatric patients by making appropriate use of physicians’ assistants, nurse practitioners, speech/language pathologists, audiologists, physical therapists and occupational therapists. “It’s important for the otolaryngologist to realize that caring for geriatric patients is a team effort and that it’s not his exclusive responsibility to rehabilitate these people but to oversee their rehabilitation,” Dr. Goldstein said.

A physician who is caring for an elderly patient with tinnitus might not only prescribe appropriate medication, but also refer the patient to a physical therapist who can provide balance therapy. Otolaryngologists who treat patients with dysphonia may perform vocal cord augmentation and refer patients for voice training; ideally, they’ll also assess the patient’s ability to communicate in daily life and work with the patient until the patient can comfortably function and interact with others.

Preparing for the Influx

Few practicing otolaryngologists received a solid medical school education in geriatrics. “The average ENT resident doesn’t get any significant training in the care of the elderly patient,” Dr. Goldstein said. Dr. Johns agreed: “When I went to medical school—and I graduated in 1996—we had absolutely no specific component of our curriculum dedicated to the care of older patients.”

Medical schools today are beginning to address that deficiency. “At Emory, we now have a specific component of our curriculum that’s dedicated to geriatric medicine, both in the foundation years and reinforced in clinical,” Dr. Johns said. “That’s a big change that is due in part to some great efforts by the American Geriatric Society and the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation, which have made a dedicated effort to improve education regarding the care of older patients.”

Physicians who did not receive specialized geriatrics education in school are well advised to pursue self-education. Professional organizations such as the American Academy of Otolaryngology and the ASGO offer a variety of conferences, online courses and tools, workshops and books to help practicing otolaryngologists better understand the needs of the geriatric population. (See “Resources on Geriatric Patients,” left.) Some states, Dr. Bhattacharyya said, now require specific CME hours in geriatric medicine.

Dr. Bhattacharyya urged practicing otolaryngologists to become familiar with geriatric otolaryngology research, particularly as it relates to their practice. “Take a look at the research involved, and make some projects for your own patient population,” Dr. Bhattacharyya said. “Make a three-year and a five-year plan. You’ve got to keep your eye on the ball, instead of waiting for the geriatric population boom to happen. It’s coming, soon.”

Leave a Reply