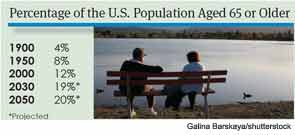

Odds are, you probably already see a fair number of older patients in your practice. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging, the number of older Americans has expanded dramatically in recent years. Between 1990 and 2009, the number of Americans older than 65 increased by almost nine million, reaching 39.6 million.

Explore This Issue

October 2012Otolaryngologists are already seeing the effects of this geriatric population boom. A 2012 study of a large, private ENT practice group in Georgia found that geriatric patient visits accounted for 14.3 percent of all patient encounters in 2004 and 17.9 percent of patient encounters in 2010 (Laryngoscope. 2012; Jul 2. doi: 10.1002/lary.23476). “The reality is that otolaryngologists already see a large portion of geriatric patients,” said Michael M. Johns III, MD, an associate professor of otolaryngology at Emory University in Atlanta and one of the authors of the study. He is also an ENT Today editorial board member.

The Administration on Aging predicts that there will be more than 72 million Americans over the age of 65 in the year 2030; Dr. Johns and his fellow researchers estimate that geriatric patients will account for a full 30 percent of all otolaryngology appointments at that time. Dr. Johns and other researchers wonder if otolaryngologists are truly equipped to handle this projected uptick. “The question is, is there enough capacity within our specialty to adequately care for these people, and are we really trained in geriatric medicine,” said Dr. Johns.

Adequate Treatment Begins with Appropriate Assessment

Dr. Johns and his colleagues found that five of the most common geriatric diagnoses, including hearing loss, vertiginous syndromes, otitis media and disorders of the inner and outer ear, are otologic. Head and neck cancer is also relatively common in the geriatric population. The average age of diagnosis for squamous cell carcinoma of the upper digestive tract is 59, and research shows that, with appropriate treatment, survival rates for geriatric patients can equal that of younger patients (Laryngoscope. 2003;113(2):368-372). Throat-related problems, including dysphonia and swallowing difficulties, are also common in the elderly (Laryngoscope. 2012;122(2):332-335).

In the past, many clinicians—and their patients—dismissed certain ear, nose and throat problems as unavoidable parts of the aging process. “When patients come in and say, ‘Doctor, my voice is a little weak,’ there’s sometimes a tendency to say, ‘Well, what do you expect? You’re 80 years old,’” said Karen Kost, MD, president of the American Society of Geriatric Otolaryngology (ASGO). “But, surprisingly often, there will be some underlying pathology. Even if no pathology is found, there’s often something we can do. We can, for instance, augment the vocal cords with injections and rehabilitate their voice, making the patient much more functional. That’s why it’s really important to listen to patients and to search for treatable conditions.”

Leave a Reply