rthimedes/shutterstock.com

Otolaryngologists will soon have an easy way to track the quality of care they provide their patients, as well as the ability to compare their efforts with local and national colleagues. This is one of many benefits of a new clinical data registry developed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNSF) and set to launch later this year.

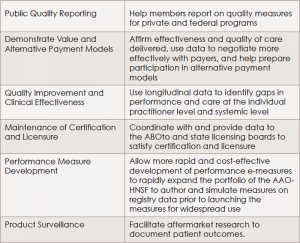

Called Regent, the clinical data registry will provide a platform for otolaryngologists to better engage in and adapt to a changing healthcare environment that is moving from volume-based care to value-based care. Within this changing environment, physicians and physician groups need to find ways to collect, analyze, and report outcomes for establishing reimbursement in a market increasingly moving toward value-based purchasing. The registry will help otolaryngologists achieve these goals (see “Benefits Offered by Regent,”).

“Payers are moving away from reimbursing for volume of care delivered to paying for quality of care and outcomes,” said Randal Weber, MD, professor, in the department of head and neck surgery at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. “Sooner rather than later, we’re all going to have to report our outcomes.” And this is where the registry can be useful, he added. “Outcomes of individual physicians will be compared with thousands of other physicians, and having data will allow us to determine the type of care our patients are receiving and whether it is the best and most appropriate care.”

The Need for a Clinical Data Registry

Improving quality is a data-driven process, according to Dr. Weber. “You have to know the data, you have to know where your outcomes data fit with the rest of the country, and then you need to determine what you can do to improve your outcomes if deficiencies are found.”

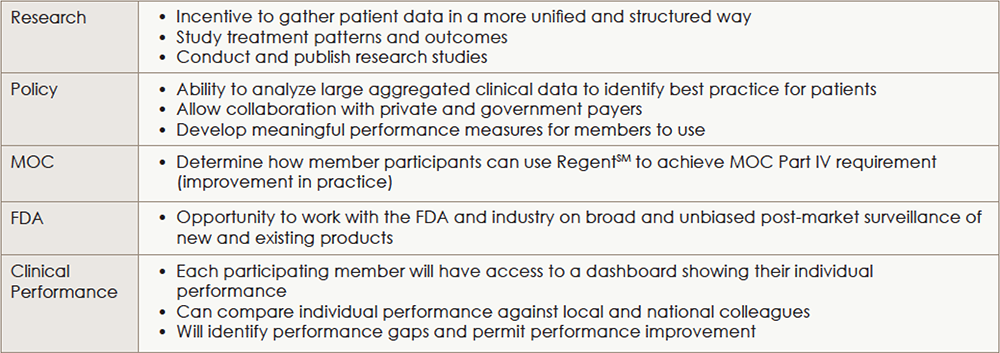

According to Lisa E. Ishii, MD, the AAO-HNSF’s coordinator for research and quality and member of the Regent Executive Committee, the database will collect clinical data, store it, and distribute it to AAO-HNS members in the form of data sets or dashboards. “Gathering data from all participating members will allow, for the first time, the analysis of large amounts of clinical otolaryngology data in aggregate.” Dr. Ishii described multiple purposes for which such aggregated data can be used to improve outcomes in otolaryngology (see “Main Uses for Collected and Aggregated Data,” p. 8).

How It Will Work

Currently, Regent is being tested at 30 pilot sites that represent a variety of otolaryngologic practices, including large and small private practice groups, academic groups, and a range of electronic medical records, said Dr. Ishii. This pilot phase will permit testing of the performance measures used in the database and ensure the accuracy and reliability of the extracted data.

(click for larger image)Benefits Offered by Regent

ABOto, American Board of Otolaryngology; AAO-HNS, American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery

Source: AAO-HNS. Regent ENT Clinical Data Registry, available at:

entnet.org/content/otoregistry.

According to Dr. Weber, the data collected by Regent will come from critical data elements captured for and generated by general otolaryngology and each subspecialty within the field. It is anticipated that these data will be electronically extracted from the providers’ electronic medical records, he said.

Dr. Weber, who is leading the development of the practice improvement module for head and neck surgery, cited the example of capturing the critical data elements that relate to taking care of patients with head and neck tumors. “These data will include outcome measures and quality measures collected across a large group of patients with different types of head and neck cancers and will be risk adjusted,” he said.

Using the established measures of quality, physicians will then enter data on their patients’ outcomes electronically into the database and will be able to see how the outcomes of their patients compare to those of other physicians treating the same type of condition. For example, Dr. Weber said that one quality measure used in treating patients with head and neck cancer is determining whether physicians ask their patients about smoking history and whether they refer all patients who do smoke to resources to help them quit. “If a physician falls below 90% referral of patients for smoking cessation, the physician would want to implement some practice changes that would help him or her meet the quality standard of 90% or greater,” he said, adding that this may take the form of, for example, an intake nurse asking patients about smoking and incorporating an automatic trigger for a referral for patients who do smoke to the appropriate treatment resource.

Dr. Weber emphasized that as practice improvement modules within otolaryngology are developed, Regent will be able to transfer individual physician data to the practice improvement module electronically, without the need to manually extract the data from the patient’s chart and input it. “Our hope is to make this easier and decrease the burden on the practitioner to collect and report data,” he said.

(click for larger image)

Main Uses for Collected and Aggregated Data

MOC, Maintenance of Certification; FDA, Food and Drug Administration.

This is also valuable in terms of part IV of maintenance of certification (MOC), he said, where data from Regent can be incorporated into the practice improvement modules and used as a quality improvement tool. During the current pilot phase, the AAO-HNSF has also applied to get approval for the database as a Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). Once certified as a QCDR, Dr. Ishii said that participating members can get credit for physician quality reporting system (PQRS).

Getting Otolaryngologists on Board

“Based on the initial great enthusiasm [more than 1,000 individuals reached out to participate in the pilot], and based on the experience of our peer organizations, we expect broad participation,” said Dr. Ishii. “Once members realize the benefits to participation in Regent, we fully expect that the vast majority of members will want to participate.” How many members will get on board will be better known once the pilot phase ends in late summer or early fall of 2016 and the database is officially launched and available to all members.

Based on the experience of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database (see Lessons Learned from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons National Database, above), David M. Shahian, MD, chair of the society’s Council on Quality, Research, and Patient Safety, encouraged otolaryngologists to view the clinical data registry as a potential aid to improving patient care and clinical practice. Emphasizing the importance of accurate data, he urged otolaryngologists to proactively engage in the database and not completely relegate data entry to someone else. “To the extent that surgeons are involved and engaged in the process of data collection, working in conjunction with their data managers, the more accurate, useful, and trustworthy the database will be to surgeons,” he said.

Mary Beth Nierengarten is a freelance medical writer based in Minnesota.

Lessons Learned from the Society for Thoracic Surgeons

Since its implementation in 1989, the Society for Thoracic Surgeons (STS) National Database has helped cardiothoracic surgeons improve quality and safety of care for their patients (Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101:841-845). “We think the STS database has been the most important factor driving performance improvement in cardiothoracic surgery over the past several decades,” said David M. Shahian, MD, chair of the STS Council on Quality, Research, and Patient Safety. “We’ve seen dramatic improvements in morbidity and mortality over the last 15 years, largely driven by the database.”

One particular area on which the database has shown an impact is performance of coronary bypass surgery. A significant improvement in the process of care, according to Dr. Shahian, is the increased use of the internal mammary artery for at least one of the bypass grafts during this surgery. Using this conduit is desirable because of its greater long-term patency and associated patient survival, said Dr. Shahian. Since hospitals and surgeons have received data from the database on the percentage of time they actually use the internal mammary artery, its use has dramatically increased, to approximately 95% or more at most programs.