Explore This Issue

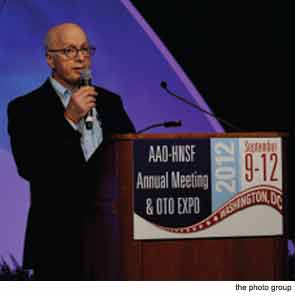

October 2012WASHINGTON—Itzhak Brook, MD, is an adjunct professor of pediatrics at Georgetown University, but when he appeared at the opening ceremony here at the 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, held Sept. 9–12, he took the stage more as a patient than as a doctor. Dr. Brook, a throat cancer survivor who now speaks with a voice prosthesis, did his best to put the otolaryngologists in the audience in their patients’ shoes—and because he’s a doctor, too, his words carried particular authority.

“In a way, I’m here for many voiceless patients,” said Dr. Brook, who gave the John Conley, MD, Lecture on Medical Ethics at the meeting. He reminded doctors of the deep emotions patients can experience while undergoing diagnosis, treatment and recovery and urged the audience to always keep that in mind, because doctors themselves can act as a patient’s most vital supporter. “Throat cancer or head and neck cancer strikes the most basic needs of a human being: the ability to communicate, eat and interact with others,” said Dr. Brook, “and losing those is really a very devastating experience.”

Dr. Brook told his story in his recently published book, My Voice: A Physician’s Personal Experience with Throat Cancer. The loss of control over his own destiny was one of the more difficult parts of his illness, he said. “I suddenly had to deal with my own mortality. I needed to deal with fear, anxiety and uncertainty of the future. I had to entrust myself in the hands of others to take care of me.”

Just finding the right doctor was stressful, he said. “If you think that I had a hard time, imagine how a lay person has difficulty making the best decision or knowing who is the best physician for them,” he said.

He urged doctors to be honest with their prospective patients. “All I can tell you is to ask yourself, are you the best person to offer the treatment and the surgery for your patient?” he said. “There may be somebody else who may offer better treatment than you.” It’s the natural inclination to want to help, he said. But he advised the physicians to “take a little bit of humility and courage” and to “encourage the patient to get a second opinion and understand the great difficulty the patient faces learning that they have cancer,” he said.

Leave a Reply