Stroke, muscular dystrophy, Parkinson’s disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), head and neck cancer, Zenker’s diverticulum—each of these disparate conditions can cause dysphagia. As our population ages, more otolaryngologists will be called upon to evaluate patients with dysphagia. In stroke patients, who tend to be older, the prevalence of dysphagia exceeds 50 percent (Cerebrovasc Dis. 2000;10(5):380-386). Undiagnosed and untreated, dysphagia can lead not only to weight loss and failure to thrive, but also to profound social and emotional problems (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(12):919-924).

Explore This Issue

February 2010Patients have no doubt when they have dysphagia, said Katherine Kendall, MD, associate professor of otolaryngology at the University of Minnesota and director of the Lions Voice Clinic at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center. “They come into your office with the complaint,” she said. “The real critical element is figuring out why they have it and what you can do to help them improve their swallowing function.”

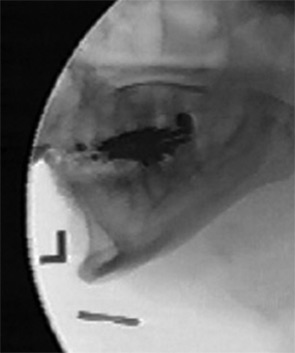

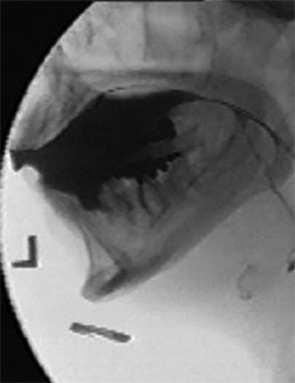

To do that, otolaryngologists use a range of diagnostic techniques, including videofluorographic swallow study (also known as a modified barium swallow study [MBS]), flexible endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) and transnasal esophagoscopy (TNE). ENToday recently spoke with several voice and swallowing disorder experts to discuss the clinical utility of these common diagnostic modalities.

Elicit Complete Information

The first diagnostic tools are a patient’s self-report, the history and the physical examination. Peter C. Belafsky, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of the Voice and Swallowing Center at the University of California at Davis (UC Davis), and colleagues advocate assessing the severity of patients’ symptoms. They have developed and validated a 10-question patient self-report dysphagia-specific outcome survey called the Eating Assessment Tool, or EAT-10. The tool, which is scored by adding patients’ ratings of their symptoms, can help establish initial symptom severity, direct treatment and evaluate therapy and surgical outcomes. An EAT-10 score of three in the setting of mild inflammation on esophagoscopy, for instance, may indicate a mild, non-erosive case of GERD amenable to management with behavioral modifications. A score of 20 indicates that dysphagia is severely affecting the patient’s quality of life and warrants an aggressive team approach for diagnosis and treatment. The tool helps to track outcomes, because it can be quickly administered and scored at each patient visit.

If you want to stack the deck in the patient’s favor, you need to know as much of the relevant history as you possibly can. A pre-fluoro history and clinical exam is essential.

If you want to stack the deck in the patient’s favor, you need to know as much of the relevant history as you possibly can. A pre-fluoro history and clinical exam is essential.—Rebecca J. Leonard, PhD

Maximizing the MBS

The MBS has become a staple in assessing the safety and effectiveness of oral and pharyngeal swallow. “But if that’s all you’re doing with this study, then you’re underutilizing it,” said Rebecca J. Leonard, PhD, professor of otolaryngology at the UC Davis Medical School and Voice and Swallowing Center. She and her colleagues recommend adhering to a standardized protocol that involves giving a patient exact amounts and consistencies of boluses of barium substances in graduated fashion, a procedure first advocated by Jeri Logemann, PhD, a professor in the departments of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and Neurology at Northwestern University who developed the MBS (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116(3):335-338). Using a standardized protocol allows a uniform means of assessing patients’ responses to treatment or changes over time and “adds greatly to the value of this study,” Dr. Leonard said.

Leave a Reply