INTRODUCTION

Explore This Issue

May 2024First described by renowned German physician Johann George Roederer in 1755, choanal atresia is an uncommon congenital anomaly in which one or both posterior nasal apertures fail to canalize, resulting in a persistent posterior plate. Etymologically derived from the Greek word χoάνη, meaning “funnel,” this anatomic space is bound anteroinferiorly by the horizontal plate of palatine bone, posterosuperiorly by the sphenoid bone, medially by the nasal septum, and laterally by the medial pterygoid plates. With a reported incidence ranging from 1 in 5,000 to 8,000 live births, the majority of cases are unilateral (65%–75%), most commonly affecting the right choana. Unilateral choanal atresia is often an indolent clinical entity, which typically presents as persistent unilateral nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea refractory to maximal medical therapy, possibly eluding definitive diagnosis for years (Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;159:920-926). Conversely, bilateral choanal atresia is suspected shortly after birth in the setting of acute respiratory failure, as neonates classically present with cyclical cyanosis, feeding difficulties, and stertor.

Ideally, the optimal surgical procedure to address choanal atresia should safely restore nasal patency, minimize damage to adjacent sinonasal structures, and eliminate reoperation with minimal disease-associated morbidity. In the modern era, the most widely accepted surgical approach that best adheres to these principles is endoscopic endonasal choanal atresia repair.

Despite these promising advancements, the reported rate of restenosis and reoperation following bilateral choanal atresia repair remains as high as 90% (Eur J Pediatr. 2021;180:2245-2251). Late-breaking studies have demonstrated promising results associated with bioabsorbable, steroid-eluting stents as an adjunct in choanal atresia repair, diminishing restenosis risk and minimizing reoperation (Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2020;129:1003-1010; J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;50:51). This work demonstrates our hybrid technique in the management of bilateral choanal atresia in a neonate by utilizing a single-stage modified endoscopic endonasal approach in conjunction with deployment of a bioabsorbable, steroid-eluting stent.

METHODS

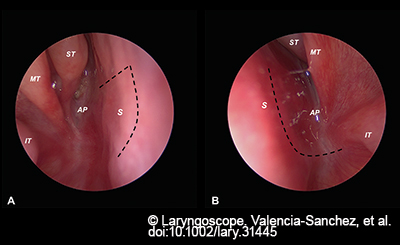

Figure 1. Nasal endoscopy demonstrating the atretic plate on each side and planned septal flap incisions (dashed black line) across the right (A) and left (B) nasal cavities. AP = atretic plate; IT = inferior turbinate; MT = middle turbinate; S = nasal septum; ST = superior turbinate.

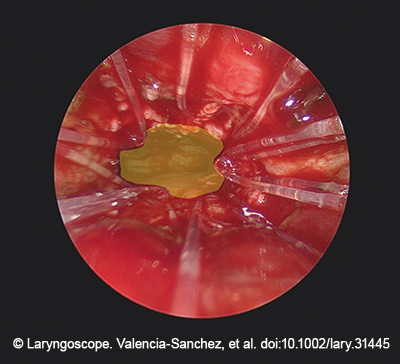

Figure 2. Nasal endoscopy reveals common neochoana patency following bioabsorbable mometasone furoate drug-eluting stent placement, which coapts both septal flaps (Propel Mini, Intersect ENT Inc.) following deployment.

Operative repair under general anesthesia was performed on day seven of life in an infant admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit without any known congenital anomalies or syndromes. Diagnostic 0-degree rigid nasal endoscopy confirmed the presence of bilateral choanal atresia (Fig. 1). The inferior turbinates were gently outfractured with a Cottle elevator to improve endonasal access. An angled needle-tip Bovie electrocautery set at 15 W was used to create L and J-shaped flaps on the left and right side of the posterior nasal septum, respectively. Of note, the inferior aspect of the middle turbinate serves as a critical landmark for both the superior extent of the posterior septal flaps and the anterior cranial fossa’s relative proximity. A Cottle elevator was used to carefully raise the L-shaped and J-shaped posterior septal flaps in a subperiosteal/mucoperichondrial plane. As described by El-Anwar and Stamm previously, the vomer and a small part of the posterior septum were resected and removed using Bellucci scissors and House micro cup forceps. The atretic plate was carefully punctured on each side at midline using a Cottle elevator and a Frazier suction, following the natural trajectory of the palatine line toward the nasopharynx to avoid inadvertent skull base injury. After the nasopharynx was clearly visualized, this was followed by complete opening toward the medial pterygoid wedge laterally using a 1 mm Kerrison rongeur. Bipolar suction electrocautery at 15 W was used to ablate excess adenoid tissue obstructing the nasopharynx and achieve meticulous hemostasis. The posterior septal flaps were then draped over exposed bone using a ball tip probe. A bioabsorbable, steroid-eluting stent (Propel Mini, Intersect ENT Inc., mometasone furoate 370 μg) was deployed into the common neochoana to ensure that septal flaps were coapted to the bony septum and nasal floor, which ensures neochoanal patency and minimizes long-term restenosis (Fig. 2).

RESULTS

Patients are immediately extubated following choanal atresia repair. Aggressive nasal saline (one spray each nostril) is administered every hour while the patient is awake, with gentle anterior suction to minimize excessive mucus buildup and sinonasal crusting. Postoperative nasal debridement is performed in office to ensure nasal patency over time. Briefly, oxymetazoline HCl is atomized endonasally to enhance nasal access. The parent or guardian is positioned in a procedure chair with the patient comfortably seated on their lap with gentle control of the patient’s arms. To prevent unexpected head motion and minimize unwanted movements, an assisting nurse holds the patient’s head. Accumulated mucus, crusts, slough, and debris from both nasal cavities are carefully removed using a 2.7 mm rigid pediatric nasal endoscope plus a Frazier suction and House alligator forceps. Depending on the patient’s clinical status, especially those with choanal atresia-associated congenital syndromes for whom a prolonged hospital stay is expected, this procedure is conducted in the neonatal intensive care unit setting. The operating room is only reserved for patients who cannot tolerate a bedside procedure, those who have planned subsequent procedures by other surgical services, or those whose family expresses that preference.

Typical postoperative follow-up periods include one to two weeks following surgery (in-office/bedside nasal debridement), four to six weeks following surgery, and every three months following initial surgery for long-term endoscopic surveillance. Most recent follow-up for this particular case confirmed a patent common neochoana with no evidence of persistent nasal obstruction, facial/nasal growth restriction, or restenosis.