© Burger/Phanie / Science Source

According to the National Sleep Foundation, 50 to 70 million Americans are affected by chronic sleep disorders and intermittent sleep problems. In-home sleep studies have become a large part of diagnosis in sleep medicine, and their presence continues to grow—a 2019 report on home sleep apnea testing devices by Global Market Insights reported that the market is set to exceed $1.4 billion by 2025. Although home tests have become more sophisticated, they may not be appropriate for some patients. It’s in the otolaryngologist’s best interest to know which is best for each patient’s needs.

Explore This Issue

September 2020Do all patients with possible sleep apnea need diagnosis in a sleep clinic? Home testing may be more comfortable and budget friendly, but its technology may miss mild obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and other sleep disorders. When appropriate, home testing enables the diagnosis of more patients, so they can begin continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) or another therapy, otolaryngologists say.

“Many patients want a home study, and they may be good candidates for one. It’s a good test and starting point for patients with high suspicion of sleep apnea,” says Pell Ann Wardrop, MD, an otolaryngologist and sleep medicine physician at CHI Saint Joseph Health in Lexington, Ky. Patients on oxygen supplementation or with some comorbidities cannot be diagnosed with home-based tests, so Dr. Wardrop believes that in-lab tests aren’t going away. Her four-bed sleep center, open since 1999, is always busy and hasn’t closed at all during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lab Versus Home

© rumruay / shutterstock.com

Typically, a physician will order a sleep study for a patient whose results on standard, short sleep questionnaires, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale or STOP-BANG test, suggest a higher likelihood that they have OSA or another sleep disorder, said Masayoshi “Mas” Takashima, MD, chair of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Houston Methodist ENT Specialists in Texas.

Sleep clinic patients generally arrive at Dr. Wardrop’s clinic at 8:30 p.m. and take a split-night study: one three-hour test to detect sleep apnea and a second test where they sleep with a CPAP or auto-PAP to adjust the mask fit and oxygen levels, said Dr. Wardrop. The clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing of OSA, published by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) in 2017, recommends the split-night testing protocol for in-lab studies. If an initial laboratory polysomnography is negative, but a clinical suspicion of OSA remains, a second in-lab test is recommended. The sleep center’s staff includes a neurologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, five full-time and two part-time sleep technicians, two registered nurses, and a certified medical assistant/receptionist.

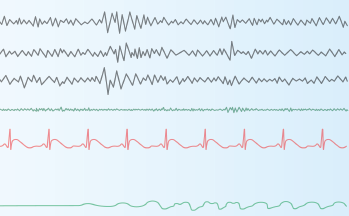

Technicians video the patient during sleep and measure 10 or more sleep parameters: sleep and sleep stages scored by at least three electroencephalogram (EEG) leads, electrocardiogram results, leg movements, respiratory flow, respiratory effort, oxygen levels, carbon dioxide levels, muscle tone, scoring, and eye movement.

At-home sleep tests generally involve a simplified breathing monitor, much like an oxygen mask, that tracks a patient’s breathing (pauses or absences) and breathing effort (whether breathing is shallow) while worn; a finger probe to determine oxygen levels; and a belt worn around the midsection, linked to the monitors. Some models also have sensors for the abdomen and chest to measure rise and fall while breathing. Most at-home sleep tests are used just for one night and returned to a sleep clinic the next day. Sleep technicians then create a detailed report based on the results.

Newer at-home models have made strides in lowering the number of contact points required, with a small monitor worn on the wrist, a pulse meter worn on the finger, and a single sensor on the chest. Some devices use a smartphone app to replace the battery and monitor, automatically transmitting results to a sleep technician through the cloud.