TKTK/SHUTTERSTOCK.com

An advisory panel to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recommended that physicians who prescribe opioid painkillers should receive training on the risks of overusing immediate release (IR), extended-release (ER), and long-acting (LA) formulations of pain medications. The committee made the endorsement following a hearing held May 3–4, 2016, in which its 30 members unanimously voted to revise current ER/LA opioid analgesic Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS).

Explore This Issue

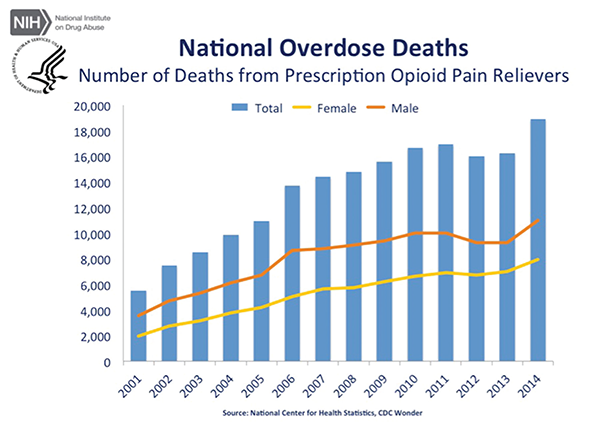

June 2016The panel made the recommendation amid an epidemic of deaths resulting from and addictions to opioid painkillers in the United States. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), almost 19,000 deaths involved prescription opioids in 2014—an increase from approximately 16,000 deaths in 2013.

In commenting on the recommendation, Anna H. Messner, MD, professor and vice chair, and residency program director of otolaryngology-head and neck surgery at Stanford Children’s Health in California, said, “It is very important for otolaryngologists to understand the benefits and limitations of any type of medication that they prescribe regularly. If the training helps to decrease the amount of opioid abuse and leads to fewer otolaryngologists prescribing narcotics when it’s not necessary, then it’s a good thing.”

Dr. Messner doesn’t think the training will have as much of an impact on pediatric otolaryngologists, however, because a recent black box warning from the FDA cautions against treating children who have sleep apnea with codeine. “Now we mostly use a combination of acetaminophen and ibuprofen to treat young children with post-tonsillectomy pain and recommend narcotics (excluding codeine) for breakthrough pain in older children and teenagers,” she said.

Source: Courtesy of National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Along these lines, Edward J. Damrose, MD, FACS, an otolaryngologist and vice chief of staff at Stanford Health Care, doesn’t think handling the issue as a one-size-fits-all approach will work. “While this problem affects all medical doctors, individual boards should administer and tailor this training to their members,” he maintained. “Otolaryngologists, who mostly manage acute surgical pain and not chronic pain, play a relatively small role in this national problem. Their training should focus on the field’s needs, such as the risks of death associated with opioid use in children and best practices in managing patients with pain from terminal cancer.”

Dr. Damrose also said that these new recommendations counter prior concepts, such as those outlined in the 2001 California legislation requiring mandatory opioid training for medical doctors. “The legislation emphasized the theme of underprescribing opioids for pain management and explored potential penalties for physicians who failed to medicate adequately,” he said. “We are now seeing the unforeseen consequences of this well-intentioned, but problematic, legislation.”

A Closer Look at the Recommendation

The two committees that comprised the panel—the FDA’s Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee and its Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee—made the recommendation because members felt that the FDA’s current opioid REMS program, which has been in effect since 2012, was unsuccessful. The program asked clinicians to voluntarily complete continuing medical education courses to learn about the risks associated with long-acting opioids.