The level of technical complexity and the stakes involved for patients make correcting facial trauma one of the most difficult tasks for head and neck surgeons. During the session “Management of Soft Tissue and Bony Facial Trauma,” a panel of experts brought their know-how and experience to the table. Here are some of their main points.

Explore This Issue

March 2015Zygomatic Bone

Stephen Park, MD, director of the division of facial plastic and reconstructive surgery at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, said fixing complex (or “tripod”) fractures to the zygomatic bone is one of the most challenging repairs to get exactly right. “Once it is fractured and displaced, the reduction is not in a linear vector,” he said. “We’re not just popping the bone out in a single dimension. You usually have to move it up and out and then rotate it to get it precisely back in position and restore facial symmetry.”

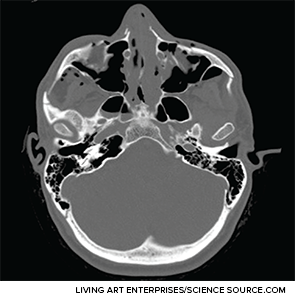

Axial CT image depicting extensive facial fractures.

To get the zygomic bone three-dimensionally and anatomically correct, he said, sometimes it is necessary to expose the zygomatic arch, the zygomatic-sphenoid fracture line, or both. The arch is the only buttress that otolaryngologists can align that sets the anterior-posterior vector, he added. Also, he said, “The zygomatic-sphenoid fracture is the only fracture that courses through all three dimensions in space, and it is your guide in complex cases.”

Craniofacial Reconstruction

Kris Moe, MD, professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery at the University of Washington in Seattle, offered three main concepts to improve outcomes in these cases.

First, he said, operate if there’s an alteration in form in function. In many cases, even with severely broken bones, this is not the case, and these considerations must be weighed by the patient. “The patient makes the decision,” Dr. Moe said.

Second, using endoscopy improves the lighting and the magnification and allows for smaller incisions and less retraction. “These things add up to more precision, less morbidity, and better outcomes,” he said.

From the audience

It was an especially good talk on dealing with high-impact injuries to facial structures in the war. Since you don’t see it commonly, it’s actually nice to hear about it from someone [who sees these injuries much more frequently].

—Jay Bhatt, MD, otolaryngology resident, University of California, Irvine

Finally, he added, virtual reconstruction using computers can be very helpful in cases in which landmarks are destroyed and a surgeon can’t see the entire fracture site. A mirror image of the other side placed digitally over the injured side provides landmarks that wouldn’t otherwise be available. A case series at his institution found that this approach improved outcomes and reduced the need for revision surgery.

High Impact Injuries in a Combat Setting

Col. Joseph Brennan, MD, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, discussed the lessons he learned reconstructing faces mangled by explosives and ripped apart by gunfire.